By THIJS BOUWKNEGT* | The Hague

Taylor awaits the dubious honor of becoming the first former head of state to be judged before an international court. But the criminal case against him on eleven counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity is in no way crystal clear. His prosecution was straitjacketed by the trial’s limited time frame, leaving many stones unturned.

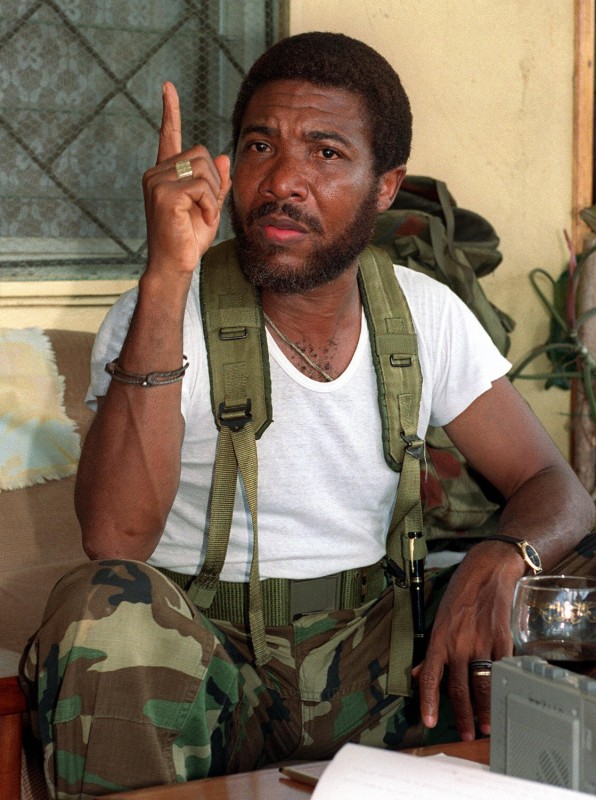

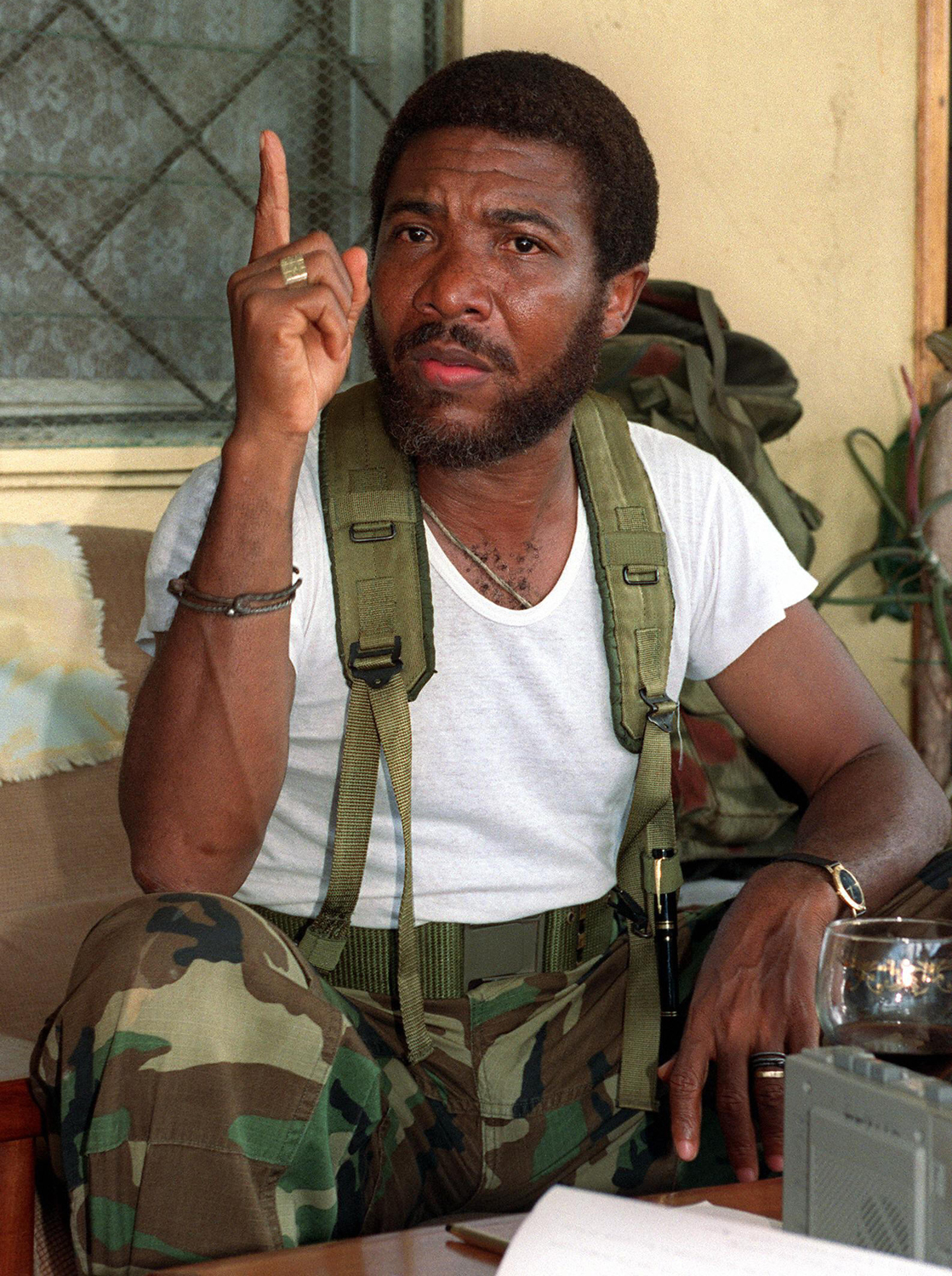

“Most definitely, Your Honour, I did not and could not have committed these acts against the sister Republic of Sierra Leone, […] so most definitely I am not guilty”, Taylor told the judges during his first appearance on April 3rd 2006 in Freetown. ‘Case SCSL-03-01’ the first case file at the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) concerned Taylor, then president. The indictment was unveiled in June 2003, while he was in Accra for peace talks prompting the Ghanaian government to fly him back to Monrovia on a presidential plane. But it was only after three years of refuge in a luxurious villa at the invitation of former Nigerian president Olegun Obasanjo that the tribunal got hold of him.

Liberia’s “Big Man” spent three months in cell number 3 at the fortified SCSL compound before being sent off to The Hague, where his trial formally began in a borrowed ICC courtroom in June 2007. Taylor fired his first lawyer Karim Kahn but did not try to frustrate further proceedings, unlike his Yugoslav cellmates in the UN prison in Scheveningen. The court even allowed him to take the stand himself for over an unprecedented seven months period, meticulously detailing West Africa’s history.

Dump the evidence

“Throw it in the bin. That is what we submit the court should do with this body of evidence: get rid of it”, said Taylor’s lead lawyer Courtenay Griffiths during closing arguments in March 2011. He argued that the conflict in Sierra Leone was not a Taylor-made catastrophe. On the contrary, he said, Taylor’s “role in Sierra Leone was entirely peaceful.”

Taylor’s ultimate crime, listed in count one of the charge sheet, echoes a post-9/11 American obsession: “acts of terrorism.” It burdened the prosecution with a complex challenge: proving that Taylor forged an illicit conspiracy with RUF leader Foday Sankoh in Libya in the late eighties to conquer West Africa. Their motive: enriching themselves with rough diamonds from Sierra Leone. Their modus operandi: a menacing campaign of terror.

Taylor does not deny an orgy of atrocities took place. He refutes the charge that he was at “the very centre of the web of these crimes.” American prosecutor Brenda Hollis continuously stressed that “the RUF was a terrorist army created and supported and directed by Charles Taylor who, in truth, is the person most responsible for the crimes charged.” “All this suffering, all these atrocities to feed the greed and lust for power of Charles Taylor,” she proclaimed.

Since 2008, the judges have listened to live testimony on how RUF rebels sowed death and destruction, pillaging diamond mines. Mustapha Mansaray, a victim of amputation, testified in a wheelchair: “Why I was willing to testify? It was for one reason. Because there was a man they used to call Charles Taylor. At the time there was war in Liberia: he said […] we would taste the bitterness of that one in Sierra Leone. What he said was what came to pass.”

Former aides and enemies

In an effort to tie Taylor to the crimes in Sierra Leone, the prosecution flew 94 witnesses to the Netherlands. The only direct evidence connecting the massacres in Sierra Leone to Taylor comes from his own former aides and enemies. Some had strong reasons for testifying against their former political rival. Others were criminals, like Joseph Marzah, known as ‘Zigzag’. The former secret service agent confessed to displaying “heads on sticks and car bumpers,” killing babies, cutting open pregnant women and eating “Nigerians and white people,” during a chaotic three-day testimony in March 2008.

The prosecution’s main battle during the trial was against time and space, as the SCSL mandate only covers crimes committed in Sierra Leone from November 1996 onwards, a period during which Taylor was in Liberia. But the prosecution argues that “the indictment crimes did not happen overnight” and focused on the alleged long-standing relationship between Taylor and the RUF. It says this bond lasted throughout the 1990s and when Taylor became president in 1997, he continued to be the “father” and “godfather” of “his proxy forces the RUF and later the RUF/AFRC.”

Some 30 witnesses testified on Taylor’s connection to the RUF and Foday Sankoh. One of them was a Gambian named Suwandi Camara who testified about one of the meetings that allegedly took place Burkina in February 2008. He said that Gambian rebel leader Kukua Sambasanja (known as Dr. Mani) and Foday Sankoh agreed to help Charles Taylor in his war. In return, he would also help them in their war, “because at that time we are very powerless,” said Camara.

RUF connections

“The RUF was in fact a creation of Charles Taylor,” insisted the prosecution. And former RUF commander Isaac Mongor testified that Taylor “had command over the RUF” and that they “took it that the RUF belonged to him [Taylor], although he sent somebody to head the RUF […] that was Foday Sankoy. “So the RUF was in the hands of Mr. Taylor,” he said. Zigzag testified in a similar vein: “We all took instructions from Charles Taylor. Have I made myself clear?”

The bond between Taylor and the RUF allegedly lasted throughout the indictment period and several of Taylor’s former aides indeed testified to regular communication between Taylor and other RUF commanders such as Sam Bockarie and the convicted Issa Sesay. The prosecution’s last linkage witness, radio operator Dauda Fornie – known as DAF – testified in December 2008 that after Sankoh was arrested there was regular communication between Taylor and the new RUF leadership, mainly Bockarie and Sesay.

“I never talked to Sankoh after May 1992”

“Complete lies”, answered Taylor. He admits to working with the RUF in the early 1990s but says it was to fight rival Liberian rebels operating on the border with Sierra Leone. “My relationship with Sankoh was a pure and simple security relationship to protect my border, that we would fight ULIMO [the United Liberation Movement of Liberia for Democracy] in Sierra Leone without having to fight them in Liberia.” But, he insisted: “I say it to these judges: I, Charles Ghankay Taylor never talked to Sankoh after May of 1992 until I saw Sankoh in 1999 July in Lomé. I did not.”

Producing almost 50,000 pages of transcript and over a thousand exhibits, the Taylor trial offers a unique insight into Liberian and Sierra Leonean history. And indeed two competing diametrically-opposed narratives about Taylor’s role in West Africa. In Taylor’s version, he is a peacemaker who is now left carrying the can for the international community, and would have had to be a “superman” to run his own war-torn country, while also planning and ordering the commission of crimes on the other side of the border. In the prosecution’s version, Taylor represents the dark corner of that world.

But the prosecution may only succeed in proving that Taylor – because of his position – “should have known” about the crimes and that he “did nothing to prevent them” while he may have been in a position to do so. The prosecutor claims he did everything to conceal his crimes and destroy evidence of links with the RUF rebels, accusing Taylor of killing his ‘favourite’ RUF general Sam Bockarie and AFRC junta leader Johnny Paul Koroma after they were also charged by the SCSL.

No meeting in Libya

Still, the bench seemed extremely compassionate towards the prosecution in allowing evidence falling outside the scope of the indictment. A lack of precision and proof were at the heart of the testimonies heard in court. And the relationship between Sankoh and Taylor in Libya – where the conspiracy was said to have started – still remains shrouded in mystery. Historian and expert witness Stephen Ellis could only relate that the two met “sometime between 1987 and 1989.” Moreover, prosecution witness Camara confirmed that he had seen Taylor twice in Libya, but that he never saw Taylor and Sankoh together.

The SCSL’s main shortcoming in this trial is that it could not deal with Taylor’s full role in West Africa’s history. Taylor’s role in Liberia’s back-to-back civil wars has been dealt with by historians and truth and reconciliation commissions in both Liberia and Sierra Leone. The Liberian TRC, in its recommendations, even drafted a statute for a Special Court for Liberia. It listed Taylor as number one suspect to be tried for alleged crimes committed in Liberia. But even though the SCSL has delved deeply into this history, it can only make findings on established crimes in Sierra Leone committed after November 1996 – leaving an era of alleged atrocities in Liberia untouched.

(*) THIJS BOUWKNEGT is a PhD researcher at the Netherlands Institute of War, Genocide and Holocaust studies (NIOD). His report first appeared on RNW .

i think it should have more educational articles like yours, so everyone would be able to learn something new.

Just wanted to comment and say that it is a very interesting news website.

Hello,My name is Vandy Kamara and currently lniivg and working ( studying) in Australia having settled here for the past four years. I went to the Huntingdon secondary school (HSS) Jui and a very proud product of that school. I would like to thank every one for still helping out there and providing the much needed help to my less fortunate brothers and sisters.I have tried over the years to get a diaspora old students association for the HSS jui but my efforts are getting me no where. I was wondering if there are any suggestions to get past students ( a lot out there) together and form this association with the aim of supporting the school back home. During my days at the school, we had students at the boarding home of the HSS from across West Africa ( Ghana, Liberia, Gambia etc) and I am sure we are scattered all over the world.Could someone help us with any suggestion/connection to keep the Jui school dream alive? Please feel free to contact me :[email protected] ( Vandy Kamara, class of 82 – 87). My constant search through social networking sites actually led me to this Huntingdon Sierra Leone Mission site. Someone please help!

Thank you for sharing some knowledge. I really appreciate it.

Comments are closed.