For many Muslims, the month of Ramadan brings them closer to Allah. In Rwanda, The AfricaPaper’s correspondent was invited to attend the nightly Taraweeh prayers at Kigali’s Islamic Cultural Centre.

Mary Katherine Keown | Rwanda

Kigali – They rise in unison, standing solemnly, shoulder to shoulder, embraced by prayer and contemplation. The imam recites verses from the Qur’an as the congregation grows, late-comers arriving with bellies full from Iftar feasts that signal an end to the day’s fast. It is Ramadan, the holy month of fasting and prayer, and I have been invited to attend the nightly Taraweeh prayers at Kigali’s Islamic Cultural Centre.

‘Gaddafi’s Mosque’

By the time the imam concludes the prayers and recitations, there are about 200 men in the cavernous white sanctuary of the mosque. Known as ‘Gaddafi’s mosque’ for the late leader who financed its construction, it sits near the end of the main road that snakes through the neighborhood of Nyamirambo, across from the city’s second-largest football field. The centre is a hub of activity.

The Islamic Cultural Centre is arguably the grandest of Kigali’s mosques, but an increasing number of sanctuaries pepper the city’s neighborhoods as Islam gains popularity throughout the country. Mahfoud el-Roinia, director of the Islamic Cultural Centre, and Isaac Munyakrazi, director of the centre’s secondary school, contend about 20 per cent of people living in Rwanda follow Islam, but most sources indicate Muslims account for approximately 14 per cent of the population, up from seven per cent before the 1994 genocide, which tore apart Rwanda at the seams and claimed at least 800,000 lives over the course of 100 days. The bloodthirsty militias, known as the Interahamwe, and other genocidaires hunted Tutsis and moderate Hutus, with the goal of complete extermination. (Some estimate more than one million people were slaughtered during the nightmare of the genocide). Men, women and children were slaughtered indiscriminately, individually or in large groups, often after seeking refuge in churches.

In search of Islam

Suleiman Kamana understands why so many have converted. Ever a man of faith, 12 years ago he replaced the Bible with the Qur’an. A life-long Christian and a Protestant pastor before the events of 1994, Kamana spent five years studying and contemplating Islam before finally converting in 2000.

“I was attracted to Islam because of the way Muslims conducted themselves in 1994,” he says. “Most did not participate in the genocide, so I was curious to find out why they did not kill. I thought maybe their book condemned such action.”

Kamana was seeking answers. He survived the genocide by taking refuge in Goma, in the North Kivu province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Many Rwandans fled during the genocide – or tried to – into the DRC, via the border towns of Gisenyi and Goma. Crossing the border saved Kamana’s life. All of his family members who stayed in Rwanda – 113 in total – were murdered during those terrible days.

He spent a year reading the Qur’an and discovered it condemns violence against others while espousing equality amongst individuals.

“Man is man and we’re all products of Adam and Eve,” Kamana explains. “If you kill your brother, you have no place in paradise.”

Witnessing Terror

As planning for the genocide got underway, Muslim leaders began denouncing violence and in 1994, witnessing the terror taking place around them, they spoke out against the propaganda fueling the war. They condemned the massacres and implored their congregations to abstain from acts of murder. Mosques were repurposed as the hunted sought refuge from the thugs and militias carrying out the genocide.

“The majority of Muslims did not participate in the genocide,” Sheikh Musa Sindayigaya, the country’s deputy mufti, says. “They announced their condemnation in local mosques, by issuing subtle messages. People pray five times per day, so this allowed leaders to convey their messages effectively.”

Roots of Islam

Introduced to Rwanda in the 19th century by traders from East Africa, Islam was initially a polarizing force, Sindayigaya says. The colonial government, which had close ties to the Catholic church, discriminated against Muslims. They were made to live in isolated settlements; they were banned from owning land, and barred from farming or rearing animals. In order to pursue higher education, Muslims were forced to adopt secular names and personas.

At independence, wishing to be free from restrictive and oppressive colonial decrees, the Muslim community sided with Tutsis, forging business partnerships and friendships.

“They faced discrimination, as well as the Tutsis. In such cases, you should get together and live together, so that you can face the challenges together,” Sindayigaya says. “This relationship extended to sharing food and sports, but not in politics, as Muslims did not participate in government. Because of the discrimination they faced under colonial rule, they were not educated and couldn’t join political parties.”

Sindayigaya, who claims that until 1994 he did not even know to which tribe he belongs, is adamant that tribe was, and remains, irrelevant. Hutus and Tutsis fought side-by-side against colonial oppression. Today, they stand shoulder-to-shoulder in the country’s mosques.

“We don’t have tribes in our religion. We have no reserved seating in the mosques. It’s ‘first come, first seated in the mosque,” he tells me. “Our system brings people together; it strengthens togetherness.”

Neighbors

Individual members of the Muslim community also offered shelter to their neighbours and friends during the 1994 genocide.

Individual members of the Muslim community also offered shelter to their neighbours and friends during the 1994 genocide.

“Muslims tried to behave positively during the genocide; they hid both Muslims and non-Muslims,” Sheikh Sindayigaya tells me.

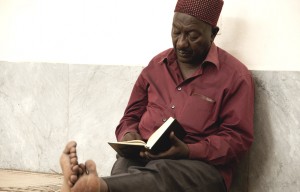

Yahaya Nsengiyumva estimates he harboured 50 people. A mechanic with Onatracom, one of Rwanda’s many bus companies, he has warm eyes, a kind smile and, at 65 years of age, the aura of someone at peace with his life. We meet at the garage where he works. Inside this urban bus yard, laden with oil-stained concrete and cluttered with rusting vehicles, the call to prayer – from the large green mosque across the street – fills the stillness of a humid August afternoon and clings to the many gas tanks and the yard’s lone tree.

Nsengiyumva, born into a family of Seventh Day Adventists, turned to Islam at the age of 15. He says the sense of community – a kinship – is a keystone in the foundation of Kigali’s Muslim community. In fact, his home was flagged as a safe haven because he was considered a community leader and many believed Tutsis would be safe in his care. Nsengiyumva tells me he did it quite simply because he loves people. He also “had a big gate,” he says matter-of-factly, which the Interahamwe could not easily penetrate. Nsengiyumva’s son, one of seven children, helped him by standing guard and brandishing weapons on occasion, in order to intimidate the roaming militias.

“I was just trying to follow the Qur’an, which tells us not to mistreat others,” Nsengiyumva says, sitting forward to emphasize his point. “My parents taught us to love everyone as creations of God. I grew up believing we’re all equal, all one.” He tells me his imam also condemned the massacres taking place throughout the country.

“It didn’t matter whether or not they were Muslim – the Qur’an teaches us we’re all equal,” He says. Nsengiyumva’s heroism is chronicled at the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre and the Rwandan Patriotic Front, the ruling party, has honoured him for his actions.

He still lives in the house he occupied in 1994 and says many of his neighbours are survivors who sought refuge under his roof.

“I’m not a hero, I did what I did because of God. All thanks should go to God,” he says modestly.

Prayers and Forgiveness

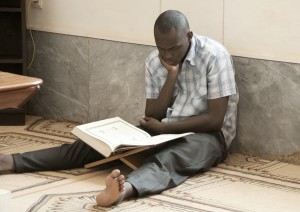

Suleiman Kamana is an ardent practitioner and these days, he relies on regular prayer for comfort, calm and communion with God.

“Your heart is clean and calm,” after praying, he explains. “Prayer is also an opportunity to seek forgiveness from God.”

We are sitting at Simba Café, a popular spot in downtown Kigali, during the month of Ramadan. Kamana is fasting, but even during the summer heat, which is relentless at mid-day, he is undeterred from his spiritual path. During a momentary lapse, I offer him a soda. He declines gracefully. Islam is his eye in the storm.

He is especially contemplative during the holy month and says it teaches adherents how to live on Earth and before God.

“It’s an opportunity to find the road again,” Kamana says. TAP