By Alex Preston | The AfricaPaper

Photos by Sunday Alamba

In northern Nigeria, radical Islamic terrorist group Boko Haram is facing a vigilante backlash from armed young men with nothing to lose. Amid the renewed optimism of this teenage uprising are fears it could push a troubled nation closer to civil war. GQ reports exclusively from a region ripped apart by violence

Two days before I landed in Maiduguri, security forces made a gruesome discovery in one of the city’s suburbs. After a tip-off, soldiers carried out a dawn raid on ten squat buildings by the sluggish river – the Ngadda – that ribbons through the city. Under a hail of bullets, they swooped on a secret stronghold of Boko Haram, the radical Islamist group that has terrorised Maiduguri, and the whole of Nigeria, for the past four years. During the gun fight, the troops killed 95 suspected Boko Haram members, arresting scores more.

Abdulkareem Haruna, a local journalist, arrived on the scene shortly after the shooting finished. He helped search the warren of underground tunnels the terrorists had dug beneath their base. “We found bodies with their hands tied together, their throats cut,” he told me. “Piles of bones; decomposing flesh. On the shelves of the huts, there were jars and containers full of blood that made us think that Boko Haram had cannibalised the bodies. Down towards the river, we came upon shallow graves. It had been raining and as the water flowed over the mud, skulls were exposed.” Another mass grave, another dark chapter in the history of one of the world’s newest and most brutal -terrorist organisations.

I travelled to Maiduguri, capital of Borno State in Nigeria’s isolated northeast, four years to the day after the violent revolt with which Boko Haram announced its jihad. I’d just spent weeks meeting Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and other NGOs. They described northern Nigeria as a warzone, with the -terrorists and the army locked in an intractable battle, heaping atrocity upon atrocity, blood soaking into the desert sands. Julia Knittel, a researcher- at Action On Armed Violence, said that her organisation had had to curtail a project tracking violence in Borno as the security situation deteriorated. “We couldn’t expose our people to that kind of risk,” she told me. “The place is a security vacuum.” The terrorists bombed busy marketplaces, slaughtered schoolchildren, enslaved thousands of women and girls; in response, the government sent its soldiers on brutal rampages, burning villages, carrying out extra-judicial executions.

We found bodies with their hands tied together, their throats cut

It was a story of unimaginable violence, and I found it staggering that Boko Haram had managed, despite the nihilism of its message and the best efforts of the fourth largest army in Africa, to bring immense tracts of northern Nigeria under its sway. Amid the carnage, I’d also heard a solitary note of hope in the shape of a vigilante gang calling itself the Civilian JTF (Joint Task Force). These loose-knit squads of young men, backed by the most powerful man in the north, the governor of Borno, were fighting, and occasionally beating, the terrorists. Hope, some said, had returned to the Nigerian Sahel for the first time in years, borne on the skinny shoulders of these teenage vigilantes.

Events in Maiduguri are of vital political importance as Nigeria heads towards elections in 2015. President Goodluck Jonathan will be judged on his ability to beat Boko Haram, and the unrest in the north threatens to deepen tribal, religious and ethnic divides that have dogged the country since independence. Jonathan is a southerner, and a Christian, and many of those I spoke to on the streets of Nigeria’s northern cities – while horrified at Boko Haram’s tactics – suggested that the group is at least sending a powerful message to the president. The Muslim north, far from the oil-drenched wealth of Lagos and Port Harcourt, feels isolated and angry, and the violence seen in Nigeria over the past few years could be a prologue to bloody collapse in 2015. As one local diplomat put it, “Finally, in Boko Haram, people in the north have found an organisation that hates the government as much as they do.”

You can’t beat fundamentalism with external force. Civilian JTF is a force from within

Boko Haram was founded by Mohammed Yusuf, the imam of a Maiduguri mosque, in 2002. Initially a local movement calling for the imposition of sharia law in northern Nigeria and the rejection of Western culture, it morphed into a jihadist terrorist organisation during the latter years of the last decade. Boko Haram has been responsible for at least 4,000 deaths and tens of thousands of casualties since 2009, when the group launched a series of vicious attacks across north and central Nigeria. Since then, the region has lurched from crisis to crisis as the Nigerian government turned the full force of its military machine on the -terrorists. In his 1979 novel about an uprising in an unnamed West African dictatorship, A Bend In The River, VS Naipaul wrote, “It isn’t that there’s no right and wrong here. There’s no right.” This is the history of Boko Haram, where every week brings fresh horror and much of it goes unreported. The Nigerian-American author Teju Cole wrote to me from Nigeria before I arrived, telling of yet another atrocity that had been swept under the carpet by the authorities. “Last week, we had news of 30 or more students in a boarding school in Yobe shot to death or burned alive by Boko Haram. In any other country, the massacre of several ten-to-12-year-olds would have been cause for serious alarm, and all normalcy in the country would be put on hold. But this story was not even carried by the national television service, the number of dead was not confirmed, and there is no evidence of an investigation. It happened last week, and it’s already vanished from the papers.”

Boko Haram translates as “Western education is forbidden”, and while this isn’t how the group refer to themselves (preferring the snappier Jama’atul Ahlis Sunnah Lidda’awati Wal Jihad), it neatly sums up their crusade against progress. The group’s spiritual leader, Mohammed Yusuf, drew large crowds to his mosque in downtown Maiduguri, mainly disenfranchised locals and wandering teenage almajiris – children sent by their parents from the wastes of the Sahel to receive Islamic instruction in the large cities. Yusuf was disowned by the Muslim establishment for his – literal – flat-earth philosophy. He -rejected belief in evolution, evaporation and the notion of a spherical globe. He also called for the imposition of sharia law, the boycotting of Nigeria’s Westernised education system, and for revolution against the country’s sclerotic, corrupt government.

In July 2009, the situation in Maiduguri unravelled with terrifying swiftness. During the funeral procession of a Boko Haram member, there was a standoff with local police, who tried to make motorcyclists in the cortege’s escort wear their helmets. It is a sign of how edgy things had become in the city that insurrection sprung from such a mundane tiff. The skittish police opened fire, wounding four Boko Haram elders. The sect had been arming itself for some time: the police were taken on, and defeated, in scenes of uncontrolled violence.

Over the last week of that bloody July, Maiduguri was a city under siege. Bodies – policemen, Christians, moderate Muslims – were piled in the car park outside Maiduguri hospital, more thrown into mass graves dug in the city’s outskirts. Some were left to rot in the streets, worried by the dogs and goats who, for several days, were the only life to be seen in the city. The Red Cross counted 780 bodies in Maiduguri alone, with hundreds more killed in neighbouring Bauchi and Yobe states. The revolt spread out from Maiduguri to take in much of north-eastern Nigeria, spreading like a bushfire through the desolate countryside, moving in ravenous leaps from one town to the next. Police stations were attacked across the region, more police killed, guns and weapons seized.

On 28 July, with the situation in Maiduguri desperate, the army was deployed to come to the aid of the hapless police force. Most of the policemen who survived the initial onslaught had quit town, overwhelmed by guerrillas who seemed to crouch behind every corner. The military acted with ruthless aggression, raining down shells on the compound in which Mohammed Yusuf had holed himself up with his acolytes. Several hundred Boko Haram fighters were killed over the next two days, until finally the compound fell. Yusuf was seized by the army, who handed him over to Maiduguri’s chief of police.

In the final hours of 30 July, the forces of the Nigerian state sowed the seeds of the violence that was to come, violence that would replicate the devastation of Maiduguri in towns and villages across the region. There is internet footage of Mohammed Yusuf, heavily bandaged, issuing a stumbling confession in a cell. An hour later, Yusuf was dead, executed without trial. While the police later claimed he’d been trying to escape, witnesses reject this. The 39-year-old Yusuf left behind four wives, 12 children and a legion of enraged followers. Worse than this, Yusuf’s assassination cleared the way for his second-in-command, Abubakar Shekau, to take control of Boko Haram.

Shekau is a sinister, shadowy figure, rumoured to have escaped from the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital in Maiduguri some time in the late Nineties. Despite Boko Haram’s eschewal of all things technological, he is a regular on YouTube, appearing in front of the group’s piratical flag clutching an AK-47 and spewing bile against Christians, the government and the evils of education. He drifts like a desert djinn along Nigeria’s borders, one day in Chad, the next in Niger, smuggling guns through the notorious Darfur Corridor. He has deepened the group’s links with Algeria’s al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and Somalia’s Al Shabaab – the two other major African terrorist organisations. Recently, the US government put a $7m bounty on his head.

Since Shekau took control of the group, Boko Haram has spun a web of terror across the north and central belt of the country, with devastating attacks on all of the regions’ major cities, regular bombings of churches and schools. Women and girls are rounded up from distant villages and forced into “temporary marriages” – Boko Haram shorthand for rape. In 2012, Shekau led Boko Haram to war in Mali, where they played a major, if losing, role in the battle against the French. They came back with guns, expertise and a thirst for blood.

Before travelling up to Maiduguri, I spent several days in Abuja meeting state officials and military sources, trying to flesh out my picture of the war against Boko Haram. A friend in England, the writer Noo Saro-Wiwa, whose father was executed by the Nigerian military dictatorship in 1995, had warned me not to expect much from these meetings. “You can’t ask questions like a normal journalist,” she said. “They just won’t respond to that. You have to let them think you’re on their side. Pose your questions carefully, and don’t expect straight answers.” Those days in Abuja come back to me now as a bad dream scripted by Kafka. The amount of time you have to wait to see someone is a sign of their status in Nigeria. So I kicked my heels for hours in the gloomy vestibules of generals, bureaucrats and politicians, staring out over Abuja’s unfinished skyline towards the National Mosque and National Christian Centre, which face each other combatively across a busy highway.

I met brigadier general Chris Olukolade in the red, black and green offices of the Nigerian Army Headquarters. A heavy, sad-eyed man, he coordinates the military response to the Boko Haram crisis. I asked him about the reports of human-rights abuses by the army in their efforts to clamp down on Boko Haram. He repeated lines I’d heard from the politicians with whom I’d had dinner the night before: that in holding terrorists without trial, in bombing remote villages they believed to be harbouring insurgents, in meeting the barbaric violence of Boko Haram with firm military muscle, Nigeria was only following a template laid down by the US and its allies in dealing with al-Qaeda. “Guantánamo” became a kind of code word in my discussions with the Nigerian military, as if American excesses on that shameful patch of Cuban soil provided an excuse for local abuses.

I told him that I’d spoken to experts on Boko Haram – Makmid Kamara at Amnesty, Eric Guttschuss of Human Rights Watch, Julia Knittel at Action On Armed Violence – all of whom had expressed significant concern at the actions of Nigerian soldiers. Olukolade frowned at me, practically spitting his next words. “Human-rights organisations, backed by foreign states, need to find evidence of brutality and military atrocities to justify their existence, to receive ongoing funding,” he said. I pressed him further. The army had gone into Baga, a town by the swiftly receding shores of Lake Chad, in pursuit of Boko Haram. Thousands of houses were destroyed, with locals describing the army as “berserkers”. Again, the brigadier general frowns, shaking his head, fixing me with those mournful eyes. “There were only nine graves in Baga,” he said. “The foreign press said 280. Nobody said nobody died, but the exaggeration was intended to paint Boko Haram as victims.” In fact, it was the Nigerian Red Cross who counted the bodies at Baga, and set the figure at 187. A local politician, Senator Maina Maaji Lawan, visited the scene of the massacre and estimated the death toll at 228. Even Olukolade had admitted in an earlier interview that almost 40 people were killed by his men, before reverting to the official government-approved figure of nine.

The brigadier general fixed me with his -mournful eyes. “The attacks on the school in Yobe,” he began, a catch in his voice. “They said they wouldn’t kill children, so they lined up the students and made them take their clothes off. The children stood there naked, afraid, and any of them with pubic hair were shot. Those who tried to escape were hunted down and executed.- Then they set the school on fire. Forty-two people were killed that day. This is what you should write about Boko Haram. This is the truth.” He picked up his BlackBerry, flipped open its Hermès case, and began to type. The interview was over. It was time for me to head north.

Flying into Maiduguri, you become aware of the engulfing vastness of the landscape. It is a city of a million people, clutched in the dusty palm of the Chad Basin, blasted by sandstorms from the Sahara. It is the sole major city in Borno State, nestling in the joint where Nigeria borders Chad, Niger and Cameroon. Maiduguri is closer to Darfur than it is to Lagos. This is a place at the very edges of human existence, facing economic depredation and an ever-encroaching desert. It is not only regularly called the most dangerous city in Africa, it is also one of the most remote.

Western journalists usually visit Maiduguri under military escort. Kidnappings are one of Boko Haram’s major sources of funding: the best you can hope for if you’re snatched by the group is several months in a malarial oubliette. More likely you’ll suffer the fate of British quantity surveyor Chris McManus who, after pleading for his life on video, was executed in the squalid dunny of the compound in which he’d been held captive for ten months. The price of freedom, at least for a French family seized in April 2013, is apparently $3m (£1.85m).

My photographer, Sunday Alamba, and I step into the yard of the airport, feeling suddenly vulnerable. I’m unconvincingly disguised as a light-skinned local, with a beard and a zawa prayer cap, a dark-grey Kanuri robe and sunglasses. I’m sweating, and it’s not only because of Maiduguri’s coruscating heat. It’s noon and 40C, massy red clouds stacking in the sky to the north. Gbenga Akingbule, our local fixer, ushers us into a burgundy BMW, which he drives as if Shekau himself is on our tail. People and goats flash by, scurrying between the umbrellas of shade provided by the dark-leaved neem trees that line the city’s streets. We pass cars whose licence plates bear Borno State’s motto: “Home of Peace”. Local wags have taken to scratching out “Peace” and replacing it with “Bombs”.

We move through checkpoint after checkpoint, some staffed by soldiers, others by the police, all of them hard-faced and inscrutable, ushering us by with the nodding muzzles of their machine guns. A procession of jeeps with Operation Restore Order emblazoned across their bonnets comes roaring up behind us, soldiers standing on the back seats, waving us aside. We pull over and watch as the jeeps race by, followed by bulky armoured vehicles, charging towards downtown Maiduguri like angry rhinos. After another checkpoint, this one bearing a turret gun that trains its eye suspiciously on us as we pass, we drive through large pink gates and into the city proper. We have arrived in Maiduguri.

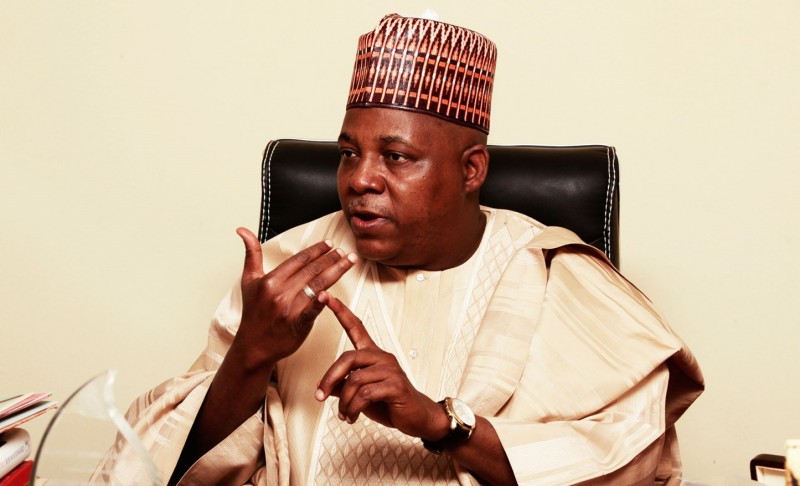

I’d expected the moment to summon a jolt of anxiety, but Maiduguri is nothing like I’d imagined it – nothing like it is presented in the Western media. I’d pictured a cloud of fear hovering over bomb-blasted buildings, nervous locals skittering from one house to the next, a sense of defeat and trauma in the eyes of the few we’d persuaded to talk to us. Instead, there’s an extraordinary energy, as if, having been confined to their homes during the months of crisis, the people of Maiduguri are making up for lost time. The streets hum with -economic activity: buildings going up on every corner, roads re-paved, queues outside market stalls. Billboards are adorned with the owlish face of the governor of Borno, Kashim Shettiman (left), with peppy slogans like “No Shaking Now”. Gbenga points out a huge construction site that the -governor has commissioned to provide affordable housing for the city’s teachers. I’d expected- many things from Maiduguri, but never this sense of optimism and civilised bustle.

It’s Ramadan, and I haven’t had anything to eat or drink since dawn in Abuja. We stop at a neem-shaded market and I buy some water. Gbenga seems to know everybody in the town, and the car is soon surrounded by teenagers with luminous grins. The locals confirm my impression that a deep and recent change has taken place in Maiduguri – they are cheerfully garrulous, slapping me on the back and laughing at my mangled attempts at Hausa, the local language. Their talk is of two things: the governor, whose work in the city they fall over each other to praise; and the Civilian JTF, the home-grown vigilantes who – they claim – have defeated Boko Haram.

I ask them how Maiduguri has come to feel so normal, so thriving. A young man with a football under his arm answers. “In the past month, the Civilian JTF has chased Boko Haram away,” he says. “Now the governor gives us jobs, gives us houses.” Another teenager puts it down to a powerful turn in the communal mind. “In the old days,” he says, “everyone would run away from a gunshot. Now we’ve become so fed up with Boko Haram that everyone runs towards it.” So far, I’ve only seen soldiers and police in the town. I want to meet these vigilantes, and ask if the young man can take us to them. “The army have forced them out of the centre,” he tells us. “They were becoming too strong, causing too many hold-ups.”

We drive out of the city and into the suburbs. The buildings here are mud-walled, some of them roofless. We edge through herds of ribby goats as veiled women stare out from doorways. Soon, the road becomes rutted and near-impassable. The boy taps Gbenga on the shoulder. At a crossroads ahead there is a blockade like many of the others we have passed through that day. Instead of soldiers, though, a posse of gangly teenagers clusters around the sandbag chicane. We sit for a while and watch them work. In place of machine guns, they have machetes, baseball bats, bows and arrows. One of the boys, wearing a Marseille football strip, is carrying a branch spiked with nails. They search the cars as they pass through, opening boots and rifling through suitcases, patting down the drivers. Motorcycles are banned in the city – they were Boko Haram’s preferred mode of transportation – but there are thousands of Chinese-manufactured tuk-tuks that act as taxis. When one of these draws up at the checkpoint, the vigilantes rock it on its haunches- until it leans at a precipitous angle and they can check the bottom for bombs.

We get out and I go to speak to the boy in the Marseille kit. His name is Abdulai and he’s 14 years old. He tells me that yesterday he went with his local chapter of the Civilian JTF to Bama, a town 43 miles from Maiduguri. They came upon a Boko Haram hideout and captured 35 militants. The terrorists had guns and rocket launchers, but were taken by surprise and overcome by sheer numbers. I ask him if he was scared. He looks at me with cool, cinematic eyes. “I’m not scared for my life,” he says.

“I’m happy to die young.” He offers to introduce me to his boss, and points me towards a tall, elegant-looking man in a teal-green tunic. We shake hands and get into the car to talk.

Boko Haram translates as ‘Western education is forbidden’

He introduces himself as Abubakar Muhammed, 27, and chairman of the Civilian JTF in the Mairi district of the city. He’d made a living selling electrical wire in the market until a Boko Haram bomb destroyed his stall. Now he speaks in a low voice, steepling his fingers and referring, touchingly, to the teenage vigilantes as his “boys”. I ask why he chose to lead the Civilian JTF. “Boko Haram came into the area, killing and setting off bombs. They destroyed 40 houses in the Mairi. My boys can no longer take it. Now it has come down to either Boko Haram kills us, or we kill Boko Haram.” I put it to him that it seems strange that kids with baseball bats have succeeded where trained soldiers failed. “The soldiers do not know Boko Haram. The soldiers are not from this place. My boys know the locals, know if someone strange moves in, if there’s something suspicious.”

There’s a brief commotion as a car tries to -circumvent the roadblock, riding up on the pavement. The vigilantes race towards it, banging on the bonnet and yelling until the car beats a cowed retreat and takes its place in the line. Abubakara tells me that many of his “boys” were unemployed before they started working for the Civilian JTF. Now there’s the hope that they, like others in the city, will be paid for their services by the governor. I offer him money as he gets out of the car, but he bats it away. “One of my boys was shot by Boko Haram yesterday. He’s in hospital now. Pray for him.”

On the road back into town, we hear the familiar roar of engines. We look round, expecting a convoy of military vehicles, but instead, coming up quickly, we see six low-slung VW Golfs, each of them on their hunkers under the weight of eight or ten members of the Civilian JTF. The boys at the back hang out of the boot and drag their machetes along the road, sending up showers of sparks. In front, the young warriors jut their chins, staring blankly forward. We find out later that the boys were heading to the town of Dikwa, halfway to the Chadian border, where they rounded up 20 Boko Haram suspects. Nineteen were delivered to military headquarters. The twentieth, a terrorist who they claimed was responsible for 70 deaths, the vigilantes took to a patch of waste ground in the city’s southern outskirts, doused him in petrol, and set him alight.

In Maiduguri, darkness falls with the swiftness of a magic trick. The slow-flying ibises that circle the city by day are replaced by enormous bats that swoop so low that you can feel the wind from their wings. At night, it becomes a frightening place again, and you can sense what it must have been like during the worst of the crisis. There’s a curfew in place and the streets are empty. Electricity is unpredictable here and most of the city sits in inky darkness, the occasional oil-drum fire sending up cones of light. Cigarettes burn on the lips of soldiers couched in the double darkness of neem-shaded checkpoints. We slap at mosquitoes, check the mirrors of the car too often, peer out into the shadow-haunted blackness.

At our hotel, we break fast with a group of local businessmen. When he hears that I’m writing about Boko Haram, a waiter leans in. “My nephew,” he says, “is in the Civilian JTF. His parents were killed by Boko Haram. You have to be crazy to take on the terrorists, to attack a man who has a gun with only a stick. It’s why it’s often the children of those murdered by Boko Haram who are fighting.” The businessmen cut in to challenge our view of Maiduguri as a city transformed. It is rather, they say, an isolated oasis, temporarily protected from the surrounding violence by the soldiers colonising the city, by the vigilance of the Civilian JTF. They tell me that vast areas of Borno remain under the control of the terrorists: villages in the Gwoza hills have been turned into Boko Haram training camps, the insurgents have disappeared into the Mandara Mountains, the Sambisa Forest on the border with Cameroon. They are still carrying out atrocities that go unreported in the press. “In the countryside, the military controls information,” one of the businessmen tells us. “They are trying to cover up the scale of the problem, to make it look like they’ve achieved victory. Many are still being killed in remote villages.” Another man speaks with a warning wag of his finger. “Maiduguri may feel safe, but Boko Haram are still here, waiting for the Civilian JTF to grow bored, to let down their guard.”

The next day, I am invited to meet the governor, though I feel like I know him already, so ubiquitous is his face on the city’s billboards. We steer through high white walls into the compound. Then, inside the palace, which is cool and dark, we are led through a labyrinth of shadowy passageways to a gloomy office, where Kashim Shettima, governor of Borno, sits behind a large walnut desk. A local man, Shettima rose from relatively humble origins to prominence first as an academic at the University of Maiduguri, then as a banker, before being elected governor in 2012. He’s in his late forties, although his round face gives the impression of someone younger. He speaks his elegantly constructed sentences with a slight lisp. “We have won the battle against Boko Haram,” he tells me, “but not the war. The war will be won not in the streets and alleys of Maiduguri, but on the factory floors. We will win by creating jobs and engaging our youths. Beneath the nihilism of Boko Haram, beneath the violence, there is the fundamental cause: extreme poverty. Any military victory we win now will be a Pyrrhic victory unless we treat the underlying cause.”

The governor is scathing about President Jonathan’s government, and specifically its response to the Boko Haram crisis. “We have not received support from the centre, and we do not expect to receive any. There is a lack of appreciation of the dynamics at play. You need to understand a problem before you deal with it. They don’t understand it.” He portrays the politicians in Abuja as entirely venal, giving me several examples – off the record – of extraordinary acts of political larceny, finishing his diatribe by quoting the great Nigerian author Chinua Achebe: “If only our leadership could rise up to meet our expectations.”

We conclude our conversation by talking about the boys of the Civilian JTF. “They are heroes,” he says, “the best thing that has happened here in the past ten years. Even if you brought in the Chinese army, you can’t beat fundamentalism with external force. This is force from within.” I mention to the governor a conversation I’d had in Abuja with Freedom Onuoha, one of President Jonathan’s closest security advisors. Onuoha had told me, in a rather poetic turn of phrase, that he was “afraid that from the womb of the Civilian JTF will come a dangerous baby”, that the vigilantes could grow to be as much of a threat to the security of the north as the terrorists they’d forced out. The governor nods. “After this euphoria is over, we want to create jobs for them. If we don’t, we will have created a Frankenstein’s monster.” They could replace the police who fled the city during the height of the crisis, I suggest. “If we call them police, the centre [ie the government] gets agitated. We will call them Public Asset Protection Squads.” Shettima gives a broad grin. “It is a wonderful thing to see: young boys with sticks chasing Boko Haram members armed with AK-47s.”

Snapshots from our remaining time in Maiduguri: a cloth-topped army truck, the back open, soldiers in black uniforms glaring at us; on the floor of the truck are three Boko Haram suspects, the only thing visible the soles of their bound feet. A training session of El Kanemi Warriors, Maiduguri’s Premier League team, who’ve played throughout the state of emergency, often with tanks at the corner flags; as the footballers bow their heads for a pre-training prayer, a crackle of machine-gun fire sounds, very close; none of them flinches. A turquoise Civilian JTF VW, its windscreen shattered, bullet holes pocking its rust-mottled flanks; outside a mosque near our hotel, lying turtled in a ditch, the husks of a burnt-out car and a tuk-tuk; relics of a recent bomb attack.

Before we leave, the governor invites us to visit some of his housing projects with him. Young men swarm across the construction site, cheering as the motorcade blasts through the gates, sirens blaring, and Shettima’s burly bodyguards jump from their vans, cradling their guns and looking warily around. The cheering increases as the governor steps from his car. Balarebe governor, the crowd cries out – his nickname is a reference to his pale skin. There is something cultish about it, the way the young men look up at him with radiant eyes. Soon there are hundreds of them mobbing the governor, holding up their hands towards him, chanting his name like a hymn or a prayer. One of the bodyguards has picked up a wooden beam; whenever the supplicants come too close he brings it down on their shoulders, on their scarred backs. Other guards stand with thick wads of thousand-naira notes, handing them out to the ardent young men.

Clouds have been massing on the horizon all day, and just as we are about to leave the housing project a storm comes up huge and red out of the Sahara. Rain is driven in wind-harried sheets and a watery darkness falls over us, illuminated every few minutes by lightning of coruscating brightness. The youths scatter as quickly as they had appeared. Sunday and I rush to the shelter of one of the governor’s cars and we pull forward with the other SUVs to form a loose corral around the unfinished school building in which the governor has taken refuge. The radio station we’d been listening to fades into a crackle of static.

It is a while before I realise that something is wrong. A convoy of military vehicles comes roaring out of the darkness and soldiers step into the deluge, shouldering their machine guns and peering around nervously. The governor’s bodyguards are also now out, scanning the perimeter of the housing project, searching among the buildings. There is something nightmarish about the darkness, and my mind -conjures spectral figures from the rain. I become convinced that, just out of sight, a swarming shadow-army lurks, waiting. Breathless minutes pass. In the momentary illumination of lightning, I see that military vehicles now line the road outside, more soldiers standing in water that is already ankle deep. This, I realise, is what it is like for the people of Maiduguri, the sense of being islanded there in the desert, the constant anticipation of bloody violence averted only by the ubiquity of the armed forces. After an hour, the storm abates, until there is only an apologetic drizzle. Whatever the threat was, it is now gone, and the soldiers climb back into their trucks and move off.

We accompany the governor to the airport. We’re heading back to Abuja; he and his wife are going on Hajj to Mecca. Dozens of the town’s worthies come to see him off, waiting to bask in the serene glow of his presence. As we board the aeroplane – an ancient Arik Air 737 with Hungarian markings – the assembled dignitaries begin to applaud, some of the younger ones cheering the governor’s name. After the storm, we rise into air that seems washed clean.

I return to Abuja with the feeling that I’ve witnessed a miracle in the desert. Only a matter of months after the city was engulfed in turmoil, the terrorists have been driven out, the vigilantes of the Civilian JTF offering hope to Maiduguri where once there was none. In the governor of Borno, the country finally seems to have a leader more interested in putting food on the tables of his people than lining his own pockets. I’d expected to find another kleptocratic satrap in a gilded palace; instead I met a man of admirable coolness in the desert heat, who spoke with intelligence and feeling about his plans for Borno’s future, achieved with or without the support of Nigeria’s government.

Peeling back the skin of the story, though, I’m left with a sense of unease that grows during the rest of my time in Abuja. The peace on the streets of Maiduguri is put down to the Civilian JTF, but everywhere you look, the -military assert their unwieldy presence. The situation feels tentative and provisional, apt to unravel at any moment. The vigilantes give a new and upbeat sheen to the struggle against Boko Haram, but this has been at core an old-fashioned story of military might against a guerrilla uprising, and history tells us that you can’t kill your way out of situations like this. Boko Haram cells have recently been reported in Niger, in Chad. One hundred suspects were captured in the south of Nigeria the week after I left. September 2013 saw the bloodiest month in more than a year, with fighting spreading to the streets of Abuja and 142 people killed in a massacre at Benisheik, western Borno. With the terrorists casting their shadows further across the breadth of the country, it is clear that the army cannot stay in Maiduguri forever.

The 2015 elections continue to glower over everything in Nigeria. President Jonathan is certain to stand again and will make sure that he wins, by fair means or foul. Depending on how blatantly the polls are manipulated, the north will either grumble loudly, or erupt in violence. Northern elders, with, at their helm, the governor of Borno, may decide that enough is enough. Some commentators have predicted civil war; others suggest that there will be a process of decentralisation whereby the northern leaders are allowed to run fiefdoms under the umbrella of the Nigerian state. Maiduguri certainly feels like it’s on the way to becoming another country; Shettima struck me as more presidential than the addled, faltering Jonathan.

We return, in the end, to the Civilian JTF. Just as Boko Haram is merely a new chapter in the history of religious violence in Nigeria, vigilantism has filled the vacuum left by the ramshackle- security services. These vigilante groups have regularly been co-opted by wily politicians into personal goon squads, roughing up opponents and intimidating voters. With Boko Haram on the back foot, at least in Maiduguri, the question lingers: what will become of the Civilian JTF, who’ve grown fond of their machetes and the power they confer? Already there are tensions emerging between the town’s various chapters, with five Civilian JTF members killed in a clash during my visit. Even more worryingly, I was told the story of Mala Othman, one of Shettima’s political rivals, whose house was attacked by a group initially thought to be Boko Haram, but later revealed as Civilian JTF. Othman escaped, but the house was torched. Shettima is too shrewd to have been directly involved, but he has not condemned the attack. What we are left with is a private army reporting to one very powerful man in the run-up to a period of political turmoil. Anywhere, it would be a recipe for trouble; in Nigeria it sounds like a catastrophe waiting to happen.

An unsteady calm reigns as I leave Nigeria. Rumours are passed around like gifts: Shekau has been seen in the Gwoza Hills; the army have wounded him; he is surrounded in a compound in the jungle. None of these appears to be true. The spectral warriors of Boko Haram still lurk in the vastness of the impoverished north, waiting to strike. There have been more attacks in the meantime, most shockingly on the Agricultural College in Damaturu, a town 80 miles west of Maiduguri, where dozens of students were massacred in their dormitories. The brouhaha surrounding the Civilian JTF may arise from the fact that, at least for now, they offer a lone note of optimism in a story that is so mired in gloom: it is a hard task to choose between the monsters of Boko Haram and those in the military sent to exterminate them. Amid the rumours, though, a few things are certain: there will be more attacks; more innocent blood spilled; more schools, churches, mosques burnt down. The build-up to the elections will be extraordinarily tense, the repercussions potentially explosive. The people of Maiduguri may come to look back on the peaceful summer of 2013, when they cheered the Civilian JTF from the city’s flat rooftops, not as the end of violence, but rather as the eye of a terrible storm.

The AfricaPaper: Many thanks to Alex Preston for this report and Sunday Alamba for all photographs.

Originally published in the February 2014 issue of British GQ.