By Hamil R. Harris | Religion Unplugged

USA – Amid arduous decades of protest, fiery oratory, and stoking the flames of Social Justice in Congress, Rep. John Lewis never forgot his call as an ordained minister of the gospel. He did what was extraordinary in the name of loving people he didn’t even know.

One day when I worked full time at The Washington Post, my cell rang, and I thought that it was my mother in Pensacola, Fla. I had no idea on the other end was Rep. Lewis, who spotted a photo of a chubby Boy Scout in uniform on my mother’s piano.

“Young man I am at your mother’s house,” said Lewis, who had been brought there by my cousin, Rev. Maurice Roland, former pastor of the John the Baptist Church in Pensacola. Roland dropped by to introduce Lewis and to meet my mother. He and Lewis were classmates at Fisk University.

I have thought about that moment since Lewis died last week. He went from Fisk, where he majored in Religion and Philosophy, to lunch counters in Nashville where he staged sit-ins with other students.

Lewis, the son of sharecroppers from Troy, Ala., would graduate from Fisk and go on to the American Baptist School of Theology and, instead of becoming a pastor, he would become the leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

In the 1960’s, he would cross paths with Rev. C.T. Vivian, 95, a veteran Civil Rights warrior, who died last week of natural causes in Atlanta. Vivian also studied at the American Baptist School of Theology in Nashville, Tenn. (now called American Baptist College).

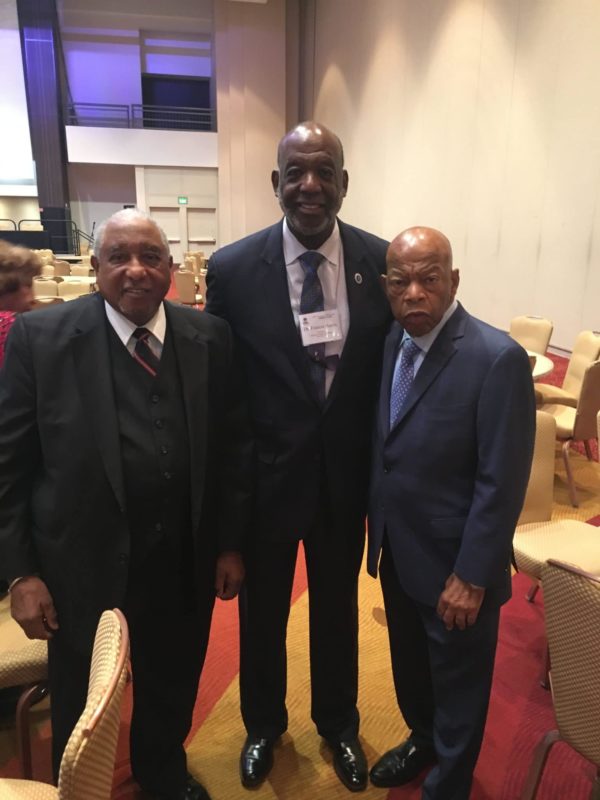

American Baptist College, and Re. John Lewis. Photo:

American Baptist College

In 1959, Lewis met James Lawson, who was teaching Gandhi’s nonviolent, direct action strategy to the Nashville Student Movement. Those who also studied about non-violence included activists Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, James Bevel and Lewis who were students at Fisk University and Tennessee State University. They would go on to organize nonviolent sit-ins at lunch counters in Nashville.

As Director of Affiliates for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Vivian’s job was to recruit local people to engage in protest in racist and segregated venues in hopes of drawing national media attention.

“I almost got killed in St. Augustine,” said Vivian in an interview I had with him backstage of the Kennedy Center when he was being honored in 2015 by the DC Choral Arts Society.

I was glued to every word because Vivian, like Lewis, was living history and I felt obligated to cover the annual musical tribute to Martin Luther King where every year veterans of the Civil Rights movement were honored from Julian Bond to Bryan Stevenson of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

I was fixed with my microphone rolling as Vivian talked about June 22, 1964, when he and other Civil Rights workers staged a “wade-in” on a segregated beach in St. Augustine, Fla. He said after being confronted by an angry mob wielding clubs, “I almost drowned.”

On June 19, three days earlier, the managers of the Monson Motor Lodge in St. Augustine poured what was thought to be acid into the pool after blacks and white protesters jumped in.

These two incidents would focus national attention on St. Augustine and helped to convinced uncommitted members of Congress to sign the Voting Rights Act of 1964.

But the battles were far from over.

On March 7, 1965, Lewis and Rev. Hosea Williams, led more than 600 peaceful protestors across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma to Montgomery in a call for voting rights for people of color in the state.

As soon as marchers crossed the Alabama River they were attacked and beaten by Alabama state troopers during a confrontation that would be known as “Bloody Sunday.”

The news of the incident was shown on TV outlets across the country and, as a result, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed the bill into law.

During the height of the Movement, from 1963 to 1966, Lewis was named Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC was largely responsible for organizing student activism in the Movement, including sit-ins and other activities.

At the age of 23, Lewis was a speaker at the historic March on Washington in August 1963, where Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

While Lewis welcomed “Good trouble,” I remember other times when he advocated for the people in such a humble way.

“Officer is it okay if we stand right here to look at the flower,” said Lewis and other members of Congress as they stood on the East front of the US Capitol and paid their respects on July 24, 1998, after United States Capitol Police officers Jacob Chestnut and Detective John Gibson were killed by Russell Eugene Weston, Jr., who entered the Capitol and opened fire.

It was early on a Saturday in October of 2003 when I met Congressman Lewis at 4th and Constitution for a stand-out interview with MSNBC about his feelings in regard to the DC Sniper driving around the Washington DC area and killing people at random.

I will never forget early Jan. 31, 2006, when I was in Jackson International Airport in Atlanta when I ran into Lewis and he told me that Coretta Scott King had died of ovarian cancer and heart failure in a small hospital in Mexico.

Moments later, I skipped my flight and my aunt took me to the Martin Luther King Center for Non-Violent Social Change where I ran into Rev. Rafael Warnock the new pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, which was led by the King family.

I reminded Warnock of the interview in the church alley as he talked about the passing of Vivian and Lewis, who was a member of Ebenezer.

“John Lewis was a spiritual giant walking among us,” Warnock said on Monday, during a phone interview. “He wrestled with the call to ministry in his youth but instead of preaching sermons he became a sermon for all the world to see.”

What stood out to me most in regard to Lewis was that he put principles over politics and for that he was respected by Republicans and Democrats. At the height of the 2008 Presidential campaign I learned during a gathering President George W. Bush hosted at the White House it wasn’t certain that Lewis was going to endorse Hillary Clinton for president.

“Call me next week,” Lewis said.

That weekend, former President Bill Clinton attended a rally for his wife at the Temple of Praise in Southeast D.C. Lewis announced, days later, that he would endorse Obama.

In what was described as a “stunning upset,” in The New York Times Lewis defeated Civil Rights Activist Julian Bond on Sep 3, 1986·to be the Democratic nominee for Congress and he would go on to beat the Republican in the heavily Democratic district.

But in 2012, Lewis and Bond joined D.C. Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton on stage at Busboys and Poets in D.C. as the greying members of SNCC talked about lessons they gleaned from the Civil Rights movement. Bond died in 2015.

“We came not out of anger but a sense of hope and faith that we could change people,” Lewis said. “We have the capacity to change and to grow and our movement was based on truth, love and reconciliation. We wanted to redeem the soul of America, a more perfect union.”

Congressman Lewis might not have preached as many sermons as other Civil Rights pastors, But he gave us numerous lessons because of the life that he led, and I will never forget him as a journalist.

The AfricaPaper/AIIR: This story was originally published by Religion Unplugged. With permission for The AfricaPaper to publish.

Hamil Harris contributes to outlets such as The Washington Post, USA Today, The Christian Chronicle and the Washington Informer. Harris is an Adjunct Professor at the University of Maryland College Park and has been a lecturer at Morgan State University. Harris is minister at the Glenarden Church of Christ and a police chaplain. A longtime reporter at The Washington Post, Harris was on the team of Post reporters that published the series “Being a Black Man.” He also was the reporter on the video project that accompanied the series that won two Emmy Awards, the Casey Medal and the Peabody Award.