By John H. Richardson | The AfricaPaper

HOW MANY BOTTLES OF WINE? How many Irish coffees? And that immense plate of seafood and the jazz band and the two pretty blond waitresses and Stan the bodyguard talking about beating down the gates of love’s palace with his purple-headed love monster. It’s a cool July night at the Green Dolphin restaurant in Cape Town, South Africa, and Nick Karras has been telling us about his private plane and his polo team and his motorcycle-racing team and his homes in California and London and his real estate development in Barbados and his twenty-two diamond mines and his “family holdings in South America” and the whole story of fishing with his father off the coast of South America all summer long until the old man went down with the boat and thirty men and someday Nick is going to sink his own boat at the very same longitude and latitude–but only after bringing the family back together and buying up the rest of the orchards in Corinth and starting a winery to revive the family tradition. And he orders another bottle of wine and tells us to eat more prawns and detours into a locker-room story about “the twins,” those little perpetual-motion machines. And finally he works his way back around to Sierra Leone, the matter at hand, where we are headed next week. With its diamonds and fish and shrimp and farmland and rutile and the most gorgeous coastline all just waiting for someone to reach in and grab it. “The UN isn’t gonna take it, the British aren’t gonna take it, we know the Sierra Leone army isn’t gonna take it,” Nick says. “It’s gotta be done privately. It’s gotta he a business.”

We are approaching Nick’s dark side. Earlier he was talking about how much the people have suffered and how much he wants to help them and all the computers and medical equipment that he’s donated. But now he’s in the mood where he says things like, “Think of them as hairless monkeys, it makes them easier to kill.” And tells (again) the story of the time that little do-gooder aid-worker girl got on his case about the diamond trade and kept saying, “Don’t you know there’s blood on those diamonds?” And finally Nick got fed up and told her, “Yeah; but it washes right off.”

He loves that line. He laughs and says it again. “Yeah, but it washes right off!”

It’s probably the wine. Which would also explain why he’s waving his hand over the giant seafood plate and insisting that no matter what happens, he’s going to carve out his piece of diamond territory and take care of things himself, establish a perimeter and plant the flag for his diamond business, Anaconda Worldwide Ltd. “Somebody’s gonna have to do it. I can tell you right now, this little area we’re gonna carve out will be done soon.”

Nick’s bodyguards, Stan and Pete, are both serious warriors, graduates of the British special services with combat experience in battlegrounds from Iraq to Bosnia. His Africa hand, James Pryor, a striking man with long hair and a personal uniform that tends toward green green fatigues, was with an elite unit of the South African army before moving to London to do political work for the prime minister he calls “Maggie.” So it definitely seems like more than bar talk when the last bottle gets low and Nick starts hinting at mysterious business with someone named Nils, something about a gunship and “a commitment to give him some money to straighten out some stuff.”

That’s when James leans forward and says, “Let’s change the subject. What is a green dolphin, anyway?”

IN THE MORNING, Nick throws back six aspirin and comes down to breakfast wearing shorts and a Hugo Boss golf shirt with his silver Dunhill pen slipped sideways between the buttons. Stan hands him an abstract of the bad news: The UN has decreed an embargo on diamonds from Sierra Leone. As of today. “Fuck it,” Nick says. “They can’t ban shit.”

He goes on about it. You can sell diamonds anywhere, sell them in New York or Israel. You can hide a million dollars’ worth in a cigarette pack and still have room left for most of the cigarettes. This is just more UN bullshit, like the five hundred blue helmets who were “captured” two months ago, who probably just dropped their weapons and ran into the woods. Because everybody knows “niggers can’t fight.” But after breakfast he goes right up to his hotel room and hunches over his laptop, skimming the latest reports. The war in Sierra Leone has been dragging on for ten years with no end in sight, a morass of banditry and regional meddling and feckless government troops all tangled around Sierra Leone’s national curse: the diamonds lying right there in the dirt, so close to the surface that all it takes to get them is a shovel and a guy with a gun to watch your back. Which is why the UN and various peace organizations came up with the label “blood diamonds” for the stones mined by the rebel armies and started publicity campaigns about how the rebels pack their wounds with cocaine to make them more frenzied and cut hands off children and babies and how they even practice cannibalism–one time, supposedly, the rebels cut slices off some guy’s face and ate them while he was still alive. They run that Cry Freetown film on CNN all the time, all those horrible images of the rebels shooting up the capital back in 1999, like it’s on regular rotation or something. The damn thing’s two years old already! And sure there’s a bit of war going on right now, but it’s really not that bad.

Or so Nick says. Because it’s bad for business. Because it’s messing with his plan. As I eventually put the story together, he was just shy of fifty, living in southern California with his wife and two kids, when he decided his personal deadline was approaching. So he added up exactly how much he would need to buy a boat at least 140 feet long, plus twenty more feet for a helicopter, plus the helicopter. Then he added a half million a year for operating expenses for thirty years and some more for living expenses and then doubled it. And then he sold everything he owned, his advertising business and home and boat and the family diamond dredges in South America, rolled all the money into a stake, and headed to Africa. He started in Guinea, but there were too many ex-communists shoving their hands into his pockets. Then he discovered Sierra Leone–man, what a country. Gorgeous diamonds. The most beautiful colored diamonds in the world. And the place was wide-open, there for the taking, just waiting for a guy like Nick Karras to come along and milk it. Ever since then he’s been racking up the frequent-flier miles from Freetown to London to Antwerp to Tel Aviv to New York, spending around half a million to as much as $2 or $3 million a trip. For every million he lays out, he makes maybe 150 grand profit. Does everything legally and pays all the fees and taxes and figures it will take him three years to make his number-if he doesn’t get killed first. He figures he has an 80 percent chance of that. But what the hell. That’s what makes it fun.

Nick closes his laptop and straps on his bulletproof vest. He’s going to meet a diamond dealer, he says. “You can’t go on this one,” he tells me. “A lot of these guys, they don’t want anyone to know when they’re doing business. They don’t even want people to know they’re in the business.”

Stan and Pete are wearing earpieces. Pete hangs behind, keeping an eye out.

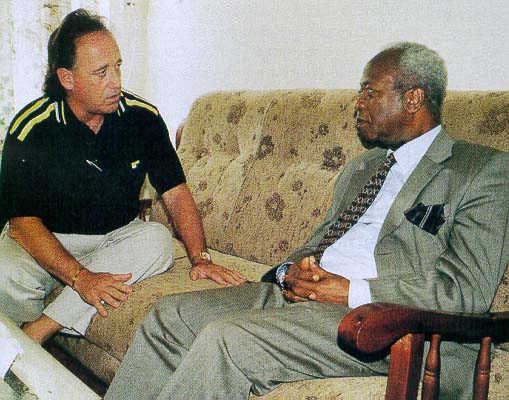

THE NEXT MORNING, Nick spends hours trying to reach Septimus Kaikai, a former economics professor at a community college outside Washington, D. C., who is now the official spokesman of the president of Sierra Leone. Nick met him a year ago and treated him and his nephew to a trip to the U. S., and they’ve been close ever since.

He comes to the table frowning. There’s no real news, he says. “The professor can’t talk on the lines because there are so many people listening.”

“Who’s listening?”

“You name it–CIA, Liberians, British. Try the springbok. It’s delicious.”

NEXT TO EATING AND DRINKING, Nick loves telling stories. Like the time he took a step into the jungle with a bag full of money and a bag full of diamonds and bumped right into natives with guns. And another time down in the Ivory Coast when some very sophisticated bandits in suits shadowed them for a couple of days and turned up in the hotel elevator, so his guys hustled him into a stairwell and gave him a gun. “And the deal is that if somebody walks through that door, start shooting, you know?”

“How much money did you have?”

“I don’t know, maybe $3 million. Not much.”

Nick’s stories go on and on and loop back on one another, weaving ing variations of Brave White Hunter around his big gut and sagging eye bags, with just enough glints of truth that you start to think Africa really does need guys like him, manly to-the-moon hustlers with the drive to will their dreams into existence. And when there are gaps in the Nickalogue, James and Stan and Pete throw in stories of their own. James telling about helicopter attacks with the Three-Two Battalion and his campaign work with the Inkatha Freedom party and Pete talking about getting stalked by a lion in Thailand and Stan–in the most droll Irish accent imaginable–throwing out glimpses of headless bodies and river pirates who attack in long canoes. And have you heard of that exciting new sport, the African high jump? “You’ve got to get all the body parts across the line,” Stan says. “Oops! It doesn’t count, you left your foot there.”

“It’s exciting,” Nick says. “It’s real exciting. You get out in the jungle sometimes at night and you wonder why you’re out there, why you’re doing it. But you’re dealing with the most precious commodity on the face of the earth and everybody wants it. A little coffee cup can hold a couple million dollars’ worth, you know? It’s exciting. I’m addicted.”

BACK IN HIS HOTEL ROOM, Nick calls me over to the window. He’s holding a piece of white tissue paper with about twenty pebbles piled in the center. They are chalky white, like something you’d find in the surf. The largest is a brownish stone about the size of a piece of pea gravel.

“This is worth probably $3,000 a carat,” Nick says.

“How many carats?”

“Twenty-two.”

“Nice,” I say. “It’s colored?”

“No, it’s just the skin on it that looks brownish like that. And here, you see that little black spot? That’s a pique, which is actually just a piece of coal.”

This is the kind of thing you can find in the riverbank gravel in Sierra Leone, Nick reminds me. The Star of Sierra Leone weighed in at 968.9 carats. Imagine living in one of the poorest countries in the world and digging up something like that. He gives me a quick lecture on the four C’s. “You can buy a round one-carat diamond for $700 or $30,000,” he says. “It’s the color, the clarity, the carat weight, and the cut. That’s what it’s all about.”

He holds up another pebble. “See how white this one is, and clear and clean?” he says. “Look at that. Look right through there. Hold it up to the light.”

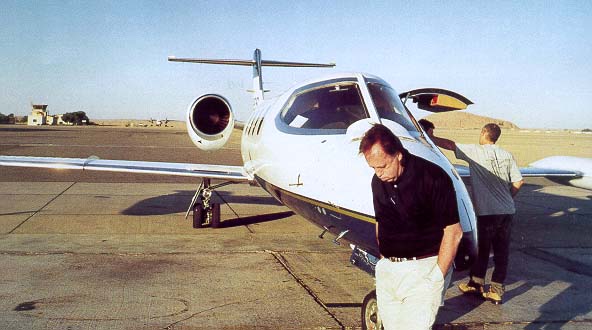

AT LUNCH THE NEXT DAY, Nick tells us the plan. This is something he enjoys and does frequently. “Tuesday morning we’re taking a private jet to Sierra Leone. It’s a really nice jet, a Learjet with a stand-up cabin, private head, the whole thing. We’re gonna make one stop on this little Portuguese island called Sao Tome It’s about 150 miles off the coast. It’s really a nice little island.” And why are we stopping there?

“To eat lunch and have a drink, man. What do you think? We got women there, you know.”

By this time, I’ve figured out that at least half of what Nick says is bullshit. When I first met him, he said he owned a private plane. Now he’s leasing one. And he said his family owned twenty-two diamond mines, but it turns out they just invested in them. Now it seems he doesn’t have a license to export diamonds from South Africa, so what he was doing with those stones in his hotel room I have no idea. The stories come too thick and fast and there’s too much food and too much drink and now we’re hitting the road in two white Mercedeses with Global Positioning Systems on the dashboards and Stan and Pete in constant touch on walkie-talkies and Nick digging around in his bag. “What have I got here?”

He pulls out a stack of greenbacks three bricks thick–$100,000.

James turns around. “Is that the money? I can smell it.”

“It’s the best smell in the world,” Stan says.

Everywhere we go, Stan carries a trauma kit stuffed with medicine and field dressings. Nick says it’s so they can stabilize him and radio the jet they keep on call. “It’s a Challenger 601,” he says. “It was actually Nelson Mandela’s private jet. And then Pavarotti used it, and then I picked it up.”

Whatever. Where’s the next bar?

At a tiny town called Taung, Nick meets with some black landowners looking for someone to help them mine their land. Nick launches into his pitch about how his family has been in the diamond-mining business for fifty-five years and they owned diamond dredges in Guyana and Venezuela and twenty-two mines and when he took over the company in 1997 he came to Africa and started in Guinea and he’d still be there if there wasn’t so much corruption, so he moved to Sierra Leone and the people love him there–he’s given equipment to hospitals and schools–and with any luck they’re going to make him the official exporter for the whole country. And last year he came down here to South Africa to start a polishing school where he’s going to teach underprivileged black people how to work diamonds and it will be bigger than anything De Beers has ever done for the people and the beginning of true integration for the diamond industry and the biggest thing the country has ever seen. Margaret Thatcher and Nelson Mandela are going to come for the opening celebration and it’s going to be huge. “We make a lot of money, and we pay a lot of taxes, but we get involved with the people personally,” Nick gushes. “It’s just the way my family’s been. When we go into a community, we do things for the hospital, for the schools, bringing in food and clothes. Sometimes it’s a lot of money, but sometimes it’s not. It’s more the thought and the spirit of what you’re doing than anything.”

Never mind that Margaret Thatcher and Nelson Mandela will be showing up for an Inkatha Freedom party celebration (if at all) and not for Nick’s factory opening, Nick keeps rubbing the word under-privileged against diamonds until they both shine bright enough to blind you. He weaves so much verbiage around his little pique of truth that it actually seems to grow into some kind of fabulous gemstone before your eyes. And maybe he even sells himself.

But it turns out that the landowners want a big investment, heavy machinery that will cost almost $3 million. That’s not what Nick had in mind. “We’d like to start with existing operations and work our way back,” Nick says. “I’m sure you understand what I’m saying. I’d like to buy some diamonds today.”

He laughs and everyone laughs with him. Then one of the landowners speaks in a soft, solemn voice. “But you see, Niko, when our MP said you were coming, we said, Thank God, now we are free. Because our land is very rich but we cannot work it. The banks say we have no experience and will not lend us the money.”

Nick backs and fills and grouses about banks but holds his ground. “You can have all the land in Africa and I can have one diamond, and I’m a richer man than you are,” he says. “You talk about being free? Money is freedom.”

IN ANTWERP TODAY, they seized a package of Sierra Leone diamonds. Which shows they’re serious about this diamond ban. And the rebels are still holding UN soldiers hostage.

And Nick is sitting down to another lunch. Back when he was in advertising, he says, the big shots used to talk down to him. “I’d say, ‘You want to continue this conversation on my boat? Maybe we could continue on your boat? You don’t have a boat? Fuck you.'”

Same thing in the diamond business. When he told his father-in-law his idea about buying in bulk, the old man told him it couldn’t be done, couldn’t be done, he’d been in this business for fifty-five years. Hell, there are Lebanese diamond dealers who wait for weeks in an office for a single stone. “We would have screaming fights,” Nick says. “I would tell him, ‘You fucking wetback. It’s a good thing your daughter’s not as big a shit as you are.’ Now he works for me.”

By the time we meet that night at the casino bar, Nick’s Evinrudes are cranked into the red. “The country is just there for the taking,” he says. “A hundred guys and a pair of gunships and you could clean out that jungle in two weeks. A month tops. It wouldn’t even cost that much.”

When Nick gets worked up like this, his head starts to twitch to the side like a dog straining at an invisible leash. He sits back with his big belly bulging into his silk golf shirt, with the fat silver Dunhill pen and the Bulgari watch and the Tiffany bracelet that comes with its own gold screwdriver, and it’s no surprise that he had his first heart attack at thirty-two, while working three phones from a bar stool. “I want to be king,” he says, cupping his balls.

As the gamblers behind us drop coins into the slots, their metronomic obsession a perfect counterpoint, Nick drinks and rants and drinks some more, gassing on about the incompetence of the UN and the uselessness of women newscasters and all the ridiculous PC bullshit regulations that stifle anyone with a little hustle-like that lazy little bitch who hauled him into court to pay her pregnancy leave and he told the judge, Why the hell should I pay for it? I didn’t knock her up!–and most especially the entire fucked-up continent of Africa, where nothing ever gets done right because it’s filled with these useless incompetents who can barely shit, shave, and shampoo without detailed instructions. “Those little islands called the United Kingdom, they conquered the whole fucking world. You know why Africa can’t do that? ‘Cause they can’t.”

By this time he’s twitching pretty hard. When he stops to breathe, he admits the whole Sierra Leone situation has got him a little stressed. “The thing is we’re on a plateau of all this shit happening,” he says, “and I’m so frustrated I just want to get my boat and check out.”

IF HE HAD HIS WAY, Nick would force the Sierra Leone government to hire mercenaries and clean out the rebels. Failing that, he has this plan–which he keeps dribbling out in mysterious hints–to hire someone to secure the area where he owns an interest in some rich mines.

The idea itself isn’t completely implausible. In 1995, a mercenary force called Executive Outcomes pushed the rebels to the border with just two hundred men. But there are a few minor sticking points. A few years ago, for instance, the rebels captured another mercenary leader named Colonel Bob McKenzie and tortured him for a few days, then ate him. Or so the story goes. I mention this to Nick in the car.

“Yeah, well, shit happens.”

Then Stan speaks up from the driver’s seat, saying that Executive Outcomes doesn’t exist anymore and we can fantasize all we want about mercenary armies but “it’s joost a lie.”

Nick leans over to confide in a low voice, “What Stan is concerned about is, we’re talking about some badass people, and it might not make me any money to shoot my mouth off. It might get me killed.”

He twitches and cups his balls.

AT BREAKFAST, Nick has a Bloody Mary. Then he has another. At lunch, he suddenly rips his menu in half.

At the mall an hour later, Nick holds up a cheap camera and asks the clerk, “Is this strong?” Just as the clerk starts to answer, Nick drops the camera onto the counter. It clatters violently on the glass.

Yesterday a diamond dealer was arrested in Congo with a million bucks and some diamonds. They took his diamonds and money and accused him of espionage. That makes Nick nervous. It makes me nervous, too. It occurs to me that tomorrow I leave for a war zone with someone who lies as often as a priest says amen. I decide that before we leave, we need to have a long and meaningful talk.

NEXT DAY, AT THE CAPE TOWN AIRPORT, Nick bristles with masculine rich-guy authority. “I do this all the time,” he tells the customs lady. “We always load the luggage directly onto the plane.” The plane is a long and sleek Lear 35 and it’s costing Nick thirty grand to rent, but it’s a hell of a way to make a splashy entrance into one of the poorest countries in the world.

We spend the night on Silo Tome and then get back on the plane, and this time there are no Bloody Marys. Instead Nick starts talking about how beautiful Sierra Leone is and how kind the people are and how much terrible suffering they have endured–and he seems to mean it. “That’s why I get off on these tangents about finishing it off,” he says. “I believe in finishing.”

As we approach Freetown, he takes out a string of silver beads and wraps-them around his hands and closes his eyes. He’s praying. The son of a bitch is praying.

And there’s the coastline of Sierra Leone, dead ahead.

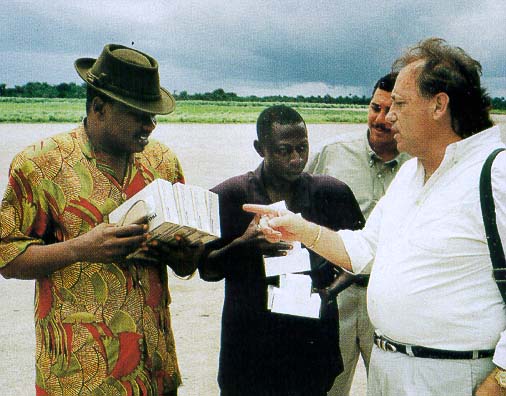

NICK STEPS OFF THE LEAR JET into a crowd of immigration and police and luggage guys and hugs and hellos and handshakes and double handshakes. “I’ve got those walkie-talkies for your guys,” he says. “Four walkie-talkies with five different channels. And who wanted the sunglasses?”

The air is moist and tropical and the warm tarmac gives off an airport smell. The landing field bustles with soldiers and UN helicopters, the pregnant kind with blades that flop over like sagging palm trees.

“And here are the battery chargers,” Nick says. “They run on rechargeable batteries, so charge ’em all night. If you don’t charge ’em all the way, then the batteries won’t last as long.”

Nick spent about $150 on these walkie-talkies, but they’re going down here like loaves and fishes. The crowd buzzes around him as if he’s Elvis Jesus Gandhi, eventually getting so big that an official comes up to protest. “This is not right, sir. This is not right, sir.

There’s no way to rationalize this.”

To break it up, Nick pushes a wad of cash on the headman. “Everybody gets small-small,” he says.

Over to the side, a group of men in uniform linger. “We’re the junior boys. He’s the senior man. We won’t get any.”

YESTERDAY THERE WAS A SKIRMISH near here. There’s also persistent trouble with a breakaway group of army soldiers called the West Side Boys. So the best way into town is a big old troop helicopter. Everybody dons headgear to mute the roar. Through the thick little windows, Freetown is a jumble of rusted tin roofs tumbling down green hills into the curve of a beautiful beach. People are lined up in the sand, hauling in fishing nets.

At the heliport, more hugs and hellos. A slender African official takes Nick’s hand in both of his. “Hello, we have so much love for you,” he says.

“I got your e-mail,” Nick says.

“I heard what you did for the man out at Lungi airport. You must do the same thing for us here. We need the communications. It is good for the development of the country.”

In Sierra Leone an American bearing gifts is everybody’s friend. The private jet helps. Small-small for everyone says the big man.

Normally Nick would spend a day in Freetown checking in with Professor Kaikai and then head up to a mountain town called Kenema, where he keeps an office run by a wild Ukrainian who lives with six local women. He’ll sit in the office for days while miners and brokers bring diamonds. But with the diamond ban on, he has no choice but to focus all his attention on his other plan: He wants to become Sierra Leone’s official business spokesman and also its official diamond exporter. He’s been talking about these schemes for days now, how he’s going to promote the wonders of Sierra Leone all over the world and also control every diamond that goes out of the country, raking millions off the top. And it seemed like just more Nickalogue. But now everything about him is serious and focused. Accompanied by his local fixers, a Guinean named Ibrahim Ghussein and Maya Kaikai, the professor’s nephew, he makes a quick stop at the hotel and heads straight downtown to meet the minister of mines-first on a long list of government officials Nick hopes to win over. He’s so intent, he’s like another person.

And Freetown is just how Nick described it. Where I expected CNN’s bullet-riddled shambles, the windy, jumbled streets are full of people and roadside stands and children playing. We pass a Catholic school that looks well tended and a Mobil station full of cars. The green hillsides are cut by hundreds of building plots waiting for new houses. This is a war zone?

But the energy sags when we get to the Ministry of Mineral Resources. Three soldiers loiter at the gate, a rooster struts in the courtyard, and the elevator can’t be trusted, so we walk up six flights of dank stairs and everywhere we look, people sit slumped over, staring into space. There seem to be at least two people at every post. A guard sleeps with his head on another guard’s shoulder.

But when they see Nick, smiles break out, followed by big hellos and hearty handshakes. Without even a moment of waiting, he goes right in to meet the minister, who sits stiffly and nods along as Nick weaves his verbal arabesques. Either he’s very tired or bored out of his mind or both. But he seems to want to make Nick happy, promising that the diamonds will certainly start flowing again by the end of the month and mentioning the possibility of restricting export licenses to “a few people or a few groups.”

It’s not exactly a promise to make Nick the official Sierra Leone exporter, but it’s in the same universe. So I ask the minister directly if he means to suggest that one of those “few people” will in fact be Nick.

He just laughs. “I’m not saying. He has applied and we’ll look at his papers alongside the Africans’.”

OUTSIDE THE OFFICE, Nick reviews. “They’re very nervous. They’re being pulled in so many different directions, they don’t want to make any commitments. And they really don’t have any money. This country is literally down to nothing.”

In fact, he says, they’re so broke they just asked him for a small contribution, something to help them attend the Diamond Council meeting in Antwerp on Monday. Just a few plane tickets. “We’re talking about basics here,” he says.

Then it’s downstairs to meet the minister of trade and industry, a thin, dignified man who seems to have a perpetual vague smile on his face. This is supposedly the man who is going to make Nick the country’s international business spokesman, so Nick launches into the whole pitch about how he came to Sierra Leone and fell in love with the place and the beauty and the people who are so gentle and how he wants to do something for them. “Not just the diamond business, but other business. Like this polishing factory that we’re doing in South Africa. We want to open a diamond-polishing factory here.”

“Mmm-hmm,” the minister says.

“And that’s going to have a trickle-down effect. I mean, we’re gonna have to supply those polishing factories, and they’re gonna have to have roads made and people are gonna need other supplies and equipment and repairs in cars and roads and trains and everything.”

“Mmm-hmm,” the minister says.

“But I’m also in the development business, the real estate development business. We’re talking about developing a couple of hotels down here, which is not a difficult thing to do for me in this country. I mean the natural beauty is incredible here.”

The minister seems mildly bemused by Nick–this oddball American with the big belly and Bulgari watch and Dunhill pen and salesman’s spiel. But he also seems–yes, he really does–to be fond of him. He’s soaking up all Nick’s horseshit like an indulgent father.

“Are you really going to make Nick an official representative of the Sierra Leone government?” I ask. “Oh, sure,” he says.

“Really?” I say. “In what capacity?”

Nick jumps in, grinning. “I wanted to be king, but he said no.” The minister frowns at me and speaks firmly, as if eager to correct my cynicism. “In the capacity of somebody who’s shared our aspirations at this very critical moment,” he says.

And that’s when it hits me–in this context, in this raped and abandoned country, a guy like Nick must seem almost lovable. After all, how many international diamond dealers parade through government offices bragging about all the money they have? How many give even a penny away? How many even bother to say a kind word?

“The exact position is gonna be determined in the very near future,” Nick says.

The minister gives him another indulgent smile. In the hallway a few minutes later, Nick heaves a satisfied sigh. Tomorrow, he sees the minister of foreign affairs. Then the vice-president. And the day after that, with any luck, the president himself. “Now we’re gonna go back to the hotel and drink,” he says.

JUST A SHORT WALK from the hotel along the crescent of the harbor is a perfect seaside bar with palm trees and a thatched roof and a patio overlooking the sand. The owner is a bluff Dutchman in a T-shirt and crew cut who brags that he closed only half a day when the rebels attacked Freetown in ’99. We lean back in white plastic chairs and admire the view. “Ah, Sierra Leone,” Stan says. “The sound of generators humming in the night.”

The service is incredibly slow, sparking various jabs at African work habits. The batik vendors who won’t go away spark a few more. Ibrahim and Maya Kaikai sit through it without a word. Just before dinner comes, a compact little man in thick glasses strolls over to say hello. He looks like a meter inspector. “This is that pilot I was telling you about,” Nick says.

It’s Nils, the gunship pilot Nick was going to pay to straighten out some stuff. Someone says something complimentary and Nils shrugs. “I’m a white man in Africa. I’m nothing.”

He tells Nick he’ll see him tomorrow at the hotel.

Over grilled fish, Nick relaxes. “Look at this cove. Can you imagine just filling this full of restaurants? They’ve got the second-largest rutile deposit in the world; if they could just get peace, in a year there’d be six or seven companies in here. In five years they’d be exporting fish, shrimp.”

IN THE MORNING, Nick goes for a walk on the beach. This is a kind of tradition with him, a declaration of purpose, a chance to represent the good life. Anyway, that’s how he explained it. Today he knocks on my door as he goes past and I jump into the shower and hurry after. As I get through the gate, a tall man in shorts approaches me. “Where’s Mr. Karras? Every morning he goes down on the beach with Stan.”

“I think they’ve already gone,” I say.

We walk together. He says his name is Guzman and he’s in the diamond business, that every morning dealers and buyers walk up and down the beach doing business. “I have a big stone,” he says. “Seventy-five carats.”

“Seventy-five carats? You have it here?”

“No, not here. I go get it. I go get it from the rebels. They’re hungry. They need to sell something and buy some weapons.”

A moment later, he bends over to show me the scar on his head. “They did this to me,” he says. “I don’t even have shoes. Nothing else. They killed my family. Everything gone. But I still hold my mind.”

Up ahead Nick is walking in his khaki shorts with his shirt open, exposing his sultanic belly, moving in the deliberate way of men who take possession of a place by walking through it. We catch up and Guzman talks to Stan for a moment and then drops behind ten paces. He seems disappointed.

THE CAPE SIERRA HOTEL is a desolate cement pile out on a well-guarded point, perhaps the safest place in all of Freetown. This is where the diamond dealers and mercenaries stay, where the journalists gather whenever the war gets particularly exciting. Every night, beautiful young prostitutes gather in the bar and if you are even vaguely polite, they will follow you halfway to your room. The patio is unfinished and there’s mold on the tennis court and out by the pool there’s a bathroom sink sitting in the grass.

This is where Nick does much of his business. This morning, he’s waiting for Nils. He won’t say what for. Apparently I have asked one too many questions about his plan to “secure an area.” And it’s possible that he got offended back in Cape Town when we had that deep and meaningful conversation and I called him a brazen, bold-faced, low-life liar. All he’ll tell me is that Nils has family in South Africa and they’re going to talk about something personal-in private. A few minutes later he slips away.

Ten minutes after that, I find him upstairs in the restaurant. I give him a big smile and sit down.

Five minutes later, he says he’s going to his room for a while. A few minutes after that, I see him walking through the lobby with Nils–off for that private chat.

THE MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS sits stiffly on the sofa, staring at the coffee table, not even looking at Nick.

Nick just sells harder. He goes through the whole pitch about his family holdings in South America and his polishing factory in South Africa and all the things he’s donated, the computers and the radios, and he just bought a sonogram machine and an X-ray machine and a heart monitor and he’s going to bring them very soon. “I want to do what I can,” he says. “I have a lot of influential, very powerful friends. I know some of the biggest businesspeople in the world. We just donated eight million leones for the war effort three weeks ago. So I wanted to let you know that I’m doing whatever I can and I’m not gonna leave you alone. I feel part of Sierra Leone.”

When there’s a lull, the minister says in the mildest of voices that his government wants to be honest. “We will not tolerate the fly-by-night businesspeople who deal with the fellows in the hotels and then fly off.”

Nick nods his head eagerly. “Like I said, I’m a businessman. If you want me to do something or go see somebody, I’ll do that. We have a very large presence in South Africa. We have an office in Cape Town. We’re spending more than a million dollars on this polishing factory. And it’s not just a polishing factory for us to polish diamonds, it’s a school for the black-empowerment movement.”

The minister smiles and asks us to sign his visitor book.

THE VICE-PRESIDENT is in a meeting, so we go to a chicken place called the Crown Bakery to wait. An hour goes by and then a stunning young woman with blond cornrows walks up to the counter. “You want her?” Nick says. “I’ll buy her for you. Ten dollars. She’s yours.”

Out on the street, you can buy hardware and building materials, and the sidewalks are overflowing with busy people. I spot a foreign woman haggling over a pair of tin snips, completely at home in an African dress. She says her name is Susan and she’s Russian and she’s been living at the Cape Sierra for three years.

“What are you doing here?” I ask.

“Business,” she says.

“The diamond business?”

“Business,” she repeats.

Back at the restaurant, Nick is giving an interview to one of the local newspapers about the walkie-talkies he donated. Then word comes from the vice-president’s office and we hop into the cars and head up into the hills, past the American embassy and the big houses overlooking the bay. The vice-president’s house is a graceless white box with an empty pool and a sandbag pillbox. A dozen soldiers guard the door. Nick goes right in.

Half an hour later, he says it went very well. “He understands the problem. We’re gonna travel together, go to meetings together-business meetings.”

Every night, people come to the Cape Sierra hoping to see Nick, some with appointments and some who press notes into your hands and look desperate. The official who estimates diamonds for the government comes once. The diamond officer from the heliport shows up two nights running, slender and solemn and glistening in the heat, talking to anyone who will listen about how much he admires Nick. “He was able to donate some amount of money, eight million leones, to the war effort,” he tells me, “and now I hear that he’s donated communication equipment to the monitoring unit of the Ministry of Mineral Resources. It is the very first time in my own capacity as an employee of the Ministry of Mineral Resources that somebody has donated such valuable equipment that can be used for the benefit of this country.”

Tonight it’s Professor Kaikai’s turn. He’s tall and lean and looks sophisticated, a man of the world. He goes straight to Nick’s suite. They talk privately for a long time. When I join them, he tells me he thinks that the diamond embargo will be lifted very soon and things are on the verge of turning around and when they do, Nick is going to be a major part of it. “He’s the kind of businessman we need in this country. He could be someplace else investing his money. He could be someplace else with his energies and his time. But he’s seen the potential in the country and he’s willing to invest a lot of his time and his money in a place like this. The fact that he was able to see the vice-president today is testimony to that.”

It’s almost like a policy statement, and Kaikai is almost too smooth, the kind of man who looks at the world through half-lidded eyes and keeps his real opinions to himself.

But there does seem to be some kind of real intimacy between them, oddly matched as they are. He mentions the day Nick donated money and computers to the vocational school and the computer he gave to the local government and the eight million leones for the war effort. Sure, that’s only about $4,000 American, but there’s another way of looking at it. “To put that in perspective,” Kaikai says, “the entire Lebanese community only donated twenty-five million leones.” It’s as if something in Nick’s blustering, hungry energy has actually touched him, not because Nick employs his nephew or because he’s fool enough to think everything Nick says is true, but because the vast effort Nick puts into coming up with all his ridiculous bullshit represents some kind of hope. “There are very few businesspeople who come into a place like this and start doing something for the people,” Kaikai tells me. “To think in terms of the people in the country and to try to actualize that is the thing I find fascinating about him.”

In the morning, Nick says the meeting with the president is up in the air. “You know, it’s the difference between ‘now-now’ and ‘just now.’ ‘Just now’ means ‘I’ll do it right now.’ ‘Now-now’ means ‘at some point.’ This is Africa, you know.”

So Nick’s going to take it easy, do some paperwork. I spend the day in town, talking to local businessmen and to a couple of newspaper editors. In contrast to the government officials I’ve been meeting with Nick, all are very fatalistic. They say the government is too weak to do anything and that diamonds corrupt every armed group that gets anywhere near them, including government troops. Including the government. Because the distinction between rebel “blood” diamonds and “legitimate” government diamonds is a fiction. Because the rebels don’t just smuggle their diamonds through Liberia, they also sell stones to the licensed diamond brokers who sell to people like Nick. The rebels control 90 percent of the diamond fields, so where else would the “legitimate” diamonds come from? They say all this in a matter-of-fact way, as if everyone knows it. Which means that for all of Nick’s talk about wanting to do good, and despite doing everything legally, he’s almost certainly been dealing in blood diamonds.

Later that day, a group of prominent local engineers laugh when I tell them Nick thinks he’s going to be Sierra Leone’s official diamond exporter. There’s no way the export licenses will be limited to one person, they say. There will be at least five. And there is some formidable competition, among them an international diamond-dealing company called the Rappaport Group, which is like Exxon to Nick’s lone rig.

That night at the hotel bar, just before dinner, the professor shows up again. Since Nick’s running a little late, I take the opportunity to ask a few rude questions. Like, isn’t it a little questionable for Nick to buy plane tickets for government officials who will vote on his export license? Kaikai smiles. “How is that different from a congressman in the United States being flown around on a corporate jet?” he says. “This is part of international business. As long as it’s up and above and there’s no strings attached, it’s all right.”

And what about the Rappaport Group? Is Nick fooling himself with this export-license thing?

He smiles again. “Let me put it to you this way,” he says. “When we were in the midst of our troubles, what did any of those people do for us? Did they contribute? Maybe they did. I’m not aware of it. De Beers was here. Did they contribute? Maybe they did. I’m not aware of it. So when you consider a smaller person who’s demonstrated an interest in the country…”

At dinner, Nils shows up with a beautiful African girl on his arm.

In the parking lot, Nick pulls Nils aside and mutters something. Nils nods and says, “Okay, get me a phone number.”

Nils’s real name is Neall Ellis and he’s fifty years old and he fought with the South African army in Angola and Rhodesia and a little bit of Mozambique but then peace brought too much paperwork and he came to Sierra Leone with Executive Outcomes. That was in ’95. He came back in ’98 with another private outfit called Sandline, him and a Lebanese guy called Hassan and an Ethiopian named Sindaba and Juba the copilot and Fred the sixty-year-old gunner. When Sandline decided to pull out, it offered them the helicopter in lieu of outstanding salaries. So they stayed and for two years they were the only helicopter gunship in Sierra Leone-maybe the only thing here as hard and real as a diamond. And Nils is pretty hard and real himself. He makes no unnecessary motions. He has a quick little smile that seems oddly disconnected down there under his thick glasses. And he seems to have very little patience for bullshit of any kind. “Until the diamond business is regulated, properly regulated, then this war will carry on,” he says flatly. “And it’s going to be very difficult to stop. I mean, even the ECOMOG and the UNAMSIL people are involved in diamond mining.”

Really? The UN troops? The troops from neighboring countries? Even the local journalists didn’t go that far.

“Well, look, I’m not saying that I’ve got proof for sure. But this is Sierra Leone. And diamonds is what makes this country talk.”

Nils is such a straight shooter that I decide to just blurt out the question on my mind. “The other day, when you and Nick went off, did Nick talk to you about securing a diamond area?”

“It depends on what you mean by securing a diamond area,” he says.

Heavy rains in the night leave a damp smell of cement rot in the hotel and all the phone lines in Freetown dead, even the lines into the army. It’ll be a slow war today. But Nick comes to breakfast saying he wants to buy a house near Cape Town that’s just unbelievable, four bedrooms and a gorgeous garden and the mountains with the grapevines and just half a million dollars and he’s going to buy some polo ponies down in Argentina-buy two hundred polo ponies and ship them to Florida and sell 180 of them and then he’d have twenty for free, see, and he’d ship those to California. And a couple to Cape Town. And look, here’s an article about him in today’s paper. “In a big move to enhancing the smooth and effective operations of the Mines Monitoring Officers in the Ministry of Mineral Resources, a United States investor Wednesday donated five handsets worth thousands of U. S. dollars…”

Then it’s time to go. At the heliport, the diamond officer who kept coming to the hotel to see Nick stands behind a rickety wooden desk in a stick hut. “He needs a new office,” Nick says. “We’re gonna build another one.”

“Please,” says the diamond officer. He waves us through.

Then the minister of mines comes in and nods to Nick and they usher him through to a private place and right behind him comes Susan, the Russian woman I ran into in the market. She’s escorting a beautiful milk-chocolate girl in chic clothes that are very tight. Then we all turn in our hand-carved wooden boarding passes and get on the helicopter, and when we get to the airport, Nick goes through another gantlet of eager baggage handlers and government officials-there’s the head of the army police and the head of the airport diamond office and Nick takes a moment with each of them, passing out money and telling the headman to give everybody small-small. An hour later we’re in Gambia.

Nick kicks back at the outdoor bar. Ahh, civlization. The Lebanese built this airport back when Gambia was a big nothing like Sierra Leone, there for the taking. Which gets Nick talking about the shrimp and the fishing and the rutile and the diamonds and his boat. And the deck where he will land his helicopter. And the helicopter. And most of all–because this is what it’s really about–the pure feeling of being a thousand miles out to sea with nothing between the sky and the water but a little speck of Nick Karras. Back in Sierra Leone he needed to care about the suffering people and so he did care about the suffering people. He really did. Nick can talk himself into anything. But that was then and this is Gambia and right now he feels gloriously free and freedom, baby, is what it’s really about. “Three years and I’m out of here,” he says. “A citizen of the world.”

Three months later, the diamond embargo was lifted, and Nick Karras was issued the very first export certificate by the government of Sierra Leone–number 000001.

The AfricaPaper: John H. Richardson was born in Washington D.C. Grew up in Athens, Manila, Saigon, Washington, Seoul, Honolulu, Los Angeles. University of Southern California ’77, Columbia University ’82. Worked at the Albuquerque Tribune, The Los Angeles Daily News, Premiere Magazine, New York Magazine, Esquire Magazine. Taught at the Columbia University, the University of New Mexico, and Purchase College. Currently Writer At Large at Esquire Magazine. Author of three books.

The Opportunist was first published in January 2001 in Esquire.