By Carmen Russell | The AfricaPaper

Philadelphia, PA – It was a day of gripping testimony Wednesday in the trial of Jucontee Thomas Woewiyu, 72, the former spokesman – and, later, Minister of Defense – for former Liberian President Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL). Woewiyu is currently charged with several immigration offenses but conviction may hinge on whether the prosecution can show he was responsible for war crimes in his native Liberia.

“I Will Kill You All”

The first to take the stand, Liberian photojournalist James Fasuekoi told the story of how he and his family evacuated from their home in Gardnesville, a suburb of the capital during the civil war. Headed for the University of Liberia Fendall Campus located along Monrovia-Kakata Highway, they encountered several checkpoints along the way, each presenting the possibility they would be killed. At one, Fasuekoi testified, a rebel soldier with the NPFL, assisted by an armed child soldier, searched their luggage finding a fired pistol shell in his uncle’s bag.

“My uncle started trembling; he was afraid,”Fasuekoi recalls. “He said, ‘I had a pistol. It was before the war.’ The rebel said, ‘I’m going to kill all of you.'”

The soldier told them to stand in a line and Fasuekoi knew death was imminent. Just as he began to look for an opportunity to “make a move and seize his weapon,” local villagers started to appear and plead for their lives.

The rebel relented and the family survived. They weren’t all so lucky later when they were apprehended again and held for several days. They were only released when Fasuekoi’s cousin – a young woman the rebel commander had taken an interest in – agreed to stay behind.

“She sacrificed herself,” Fasuekoi told the court. He never saw her again.

Photographic Evidence

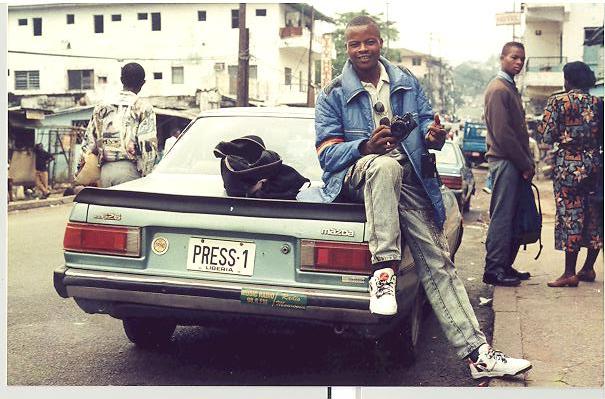

Eventually, Fasuekoi returned to his photojournalism activities, shooting the symbols of war including corpses, child soldiers, and senior rebel leadership. Many of those photos have been deemed essential to the prosecution’s effort to establish Woewiyu’s role with the NPFL and, therefore, his role in war atrocities.

[Editor’s Note: For full disclosure, James Fasuekoi is a member of The AfricaPaper staff. The AfricaPaper and AIIR holds one of the largest collections of West Africa war photographs. Fasuekoi was subpoena by the court to testify in Jucontee Thomas Woewiyu’s case.]

As his photos of the defendant were presented to the jury, Assistant US Attorney Linwood C. Wright, Jr asked Fasuekoi to confirm the identity of subjects in the photos – some of himself, some of victims of the war, some of children posing with large rifles. Of particular interest to the court are the clear shots a younger Woewiyu, speaking to crowds or standing next to other faction leaders and members of the NPFL.

In one, Woewiyu holds a microphone talking to – as Fasuekoi explains – members of the foreign press to announce the opening of roads into and out of Monrovia. Monrovia, still being controlled by government forces, was largely cut off from the rest of the country which had become less-than-affectionately known as Taylor Land, after NPFL’s leader – and Woewiyu’s boss – Charles Taylor.

“It was forbidden to leave from the other side but, for some reason, the NPFL decided to open the roads so they had this elaborate event [to announce it],” Fasuekoi told the court. Asked about another photo showing large crowds at the announcement, Fasuekoi further explained that “People had been anticipating it greatly because they had been cut off from their family for almost two years.”

The opening was temporary, however, and Taylor’s forces soon went back to shelling the capital, eventually taking control.

In finale, Wright asked Fasuekoi if Woewiyu was sitting in the courtroom.

“Yes,” Fasuekoi responded. “He is wearing a blue, maybe dark blue coat and a red tie.”

“Let the record show the witness has identified the defendant,” Judge Anita Brody said.

NPFL Spokesman

Following Fasuekoi, the government brought two representatives of the US State Department to the stand. Both testified to communications they had with Woewiyu, helping the prosecution demonstrate that he spoke for the NPFL and led its armed contingent.

James K. Bishop, who served as the US ambassador to Liberia, started his term the day Samuel Doe’s coup brought him to power in 1980. He was scheduled to be transferred from the post after the start of the war.

While attempting to organize peace talks between the NPFL and government forces, there was no doubt who would be present for NPFL.

“We were informed that Thomas Woewiyu was going to engage in the talks that we had in mind,” Bishop said. He later explained that he was given clear indication that Woewiyu also served as Minister of Defense “or some such title” but, whatever the title was, he was “in charge of the military.”

Legal Strategy

Jucontee Thomas Woewiyu has lived in the United States for nearly 50 years, returning home to Liberia to help in Charles Taylor’s coup in the 1980s. Woewiyu has never been charged with crimes specifically related to that effort in Liberia or elsewhere. Even in this case, prosecutors are focusing on questions of immigration fraud stemming from whether Woewiyu was required to make his NPFL activities clear on his application for citizenship.

The prosecution contends that he committed fraud by omitting that information, a contention bolstered by the fact that his application would likely have been rejected if he had.

“You can’t commit human rights abuses in your own country and come here and expect to obtain citizenship,” Assistant US Attorney Nelson S. T. Thayer Jr. said in the prosecution’s opening remarks on Tuesday.

However, the defense contends that the US District Court for Eastern Pennsylvania is the wrong venue for adjudicating Woewiyu’s activities from more than 20 years ago.

“Perhaps they genuinely want to hold someone accountable for the trauma the Liberian citizens experienced in Africa three decades ago,” Woewiyu’s lawyer Catherine Henry said in opening remarks for the defense. “But the United States doesn’t have the jurisdiction to prosecute war crimes that happened in Africa. There’s nothing they can do in this courtroom to change that.”

The prosecution has a reason to feel confident, however: A jury in the same court convicted another former Liberian warlord, Mohammed Jabateh, last year, for very similar charges. One possibly key difference likes in the fact Jabateh was seeking asylum and residency, claiming he faced grave danger in Liberia – an ironic contention given his proclivities. Woewiyu, however, already had permanent residency and the defense contends he did not try to hide his Liberian activities.